A FEASIBILITY STUDY OF NARRATIVE MEDICINE INTERVENTION IN AN INTERNAL MEDICINE RESIDENCY PROGRAM | Faiz Jiwani, Rebecca Rosero, Deepa Dongarwar, Larry Laufman, R. Michelle Schmidt

Abstract

Narrative Medicine curriculum can advance key clinical skills during medical school and residency training. This study examined the acceptability of a narrative medicine curriculum among Internal Medicine residents across all years of training. Participants for this study included an intervention group and a comparison group of residents from a large, academic internal medicine residency program. The intervention group underwent four consecutive one-hour weekly narrative medicine workshops, which included group discussion of a creative work, structured individual reflective writing, and further discussion. Both the intervention and comparison group completed a pre- and post-survey consisting of demographic information and the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI). The intervention group was also asked about subjective experiences of the workshop. Analysis revealed 60% of participants of the narrative medicine workshop indicated the workshop as enjoyable, an activity they would attend again, as well as one they believed was a valuable instrument for patient care. Though not powered for such analysis, a small increase in empathic concern, a subscale of the IRI, among the intervention group of internal medicine residents hints at a potential positive effect of a narrative medicine exposure. This pilot study clearly demonstrated the acceptability of this narrative medicine experience within the residency program curriculum in addition to suggesting potential value for physician education and patient care.

Literature Review

Medical Education

Since the publication of the Flexner report in 1910, medical education has undergone various improvements [1]. New emphases on person-centered care, cultural competency, and interprofessional education have prompted changes in American College of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) accreditation criteria. In February 1999, the ACGME introduced the Outcomes Project, which conditioned accreditation on including specific competencies in residency evaluations including, among others, “interpersonal and communication skills” [2]. This change heralded similar changes to MCAT design.

Narrative Medicine in Medical Education

Narrative medicine is one approach to improve these clinical skills, which is increasingly utilized by medical school and residency programs. While the phrase narrative medicine is used to describe various practices involving medical writing and patient narratives, narrative medicine here denotes the field stemming from the work of Dr. Rita Charon, which envisions medical care suffused with “narrative competence,” or the ability to “acknowledge, absorb, interpret, and act on the stories and plights of others” [3].

The positive effects of Narrative Medicine on medical trainees continue to be investigated. Narrative competence may reinforce various aspects of clinical care, including sensitivity to the descriptive detail in the accounts of illness which patients give their healthcare providers. Charon describes this as the skill of diagnostic listening or, put more simply, attention [4]. A similar benefit, generative empathy, is defined as “the inner experience of sharing in and comprehending the momentary psychological state of another person...experiencing in some fashion the feelings of another person" [4]. Thus, participation in a narrative medicine curriculum may better equip residents to dialogue with patients, improving both their clinical care and patient satisfaction with medical care.

Empathy and Narrative Medicine

While the term is widely used throughout medical literature, there are various descriptions of empathy. Another study defines physician empathy as the “physician’s understanding of the patient and verbal and non-verbal communication of the physician resulting in a helpful therapeutic action” [5]. Declining empathy has been repeatedly demonstrated during usual clinical training [6,7] and, therefore, may be addressed by narrative medicine. While this decline has not been attributed to any particular aspect of medical education, there are some relevant findings in small studies. McFarland et al [8]. found that exposure to moments of high distress and death during an inpatient hematology-oncology rotation led to declines in measured empathy among internal medicine resident physicians [8]. One study of medical students found an inverse association between empathic concern and burnout [9].

Given these potential benefits, various approaches to cultivating narrative competence in healthcare providers and trainees have been described in both clinical and interprofessional settings. One systematic review of empathy training in medical students found that of eighteen studies, four reported an improvement in measurable empathy when using narrative interventions [10]. Most often, these interventions feature close reading of literature or close observation of visual art and subsequent reflective writing, completed in structured and unstructured settings. There are challenges, some predictable, to implementing narrative medical writing in the internal medicine context, with Liao, et al. noting the complexity of clinical scheduling and limitations that duty hour restrictions place on additional didactics, supporting the use of existing structured didactic time whenever possible [11].

The Narrative Medicine Workshop

While the paradigm of narrative medicine has inspired numerous applications, the foremost and perhaps best-studied tool is the narrative medicine workshop. This approach has been implemented in various academic ambulatory clinical settings with positive effects on team morale and interprofessional dialogue. Gowda et al. [12], of which one of the authors was a part, found that monthly narrative medicine workshops in academic primary care clinics garnered active participation and was accepted by participants, with 94% of staff members recommending the workshop to other clinics and 74% expressing interest in continued sessions during their free time [12]. In this study, several participants also reflected positively during interviews on discussion “across professions and levels of hierarchy that had not occurred with other prior team-building activities at the clinic” [12]. Similar approaches have been accepted among small groups of medical students as well as trainees in an internal medicine residency program [13, 14, 15, 16] with at least one study showing a possible impact on measured empathy scores [16].

Measurement of Empathy and the Interpersonal Reactivity Index

First introduced in 1980, the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI) consists of four seven-item subscales designed for the general population to assess empathy using multiple constructs. Specifically, these constructs are (1) attempts to take on the perspectives of others (perspective-taking), (2) the “tendency to identify” with fictional characters (fantasy), (3) “feelings of warmth, compassion, and concern for others,” (empathic concern) and (4) “personal feelings of anxiety and discomfort” from witnessing the negative experience of another (personal distress) [17]. The IRI exhibits similar subscale correlations in both men and women and substantial temporal reliability. Several studies have looked at the validity of the IRI between genders, among medical students [18]. A meta-analysis demonstrated that looking at 50 studies and 23 instruments concluded that there is no gold-standard instrument to measure empathy [19]. Another study demonstrated that two subscales, empathic concern and perspective taking, of the IRI, which was developed for the general population had more relevance to patient care similar to other instruments developed to measure empathy specific to health care providers [20].

Purpose

In this pilot study, a narrative medicine workshop series was held for internal medical residents. This study aims to (1) establish site-specific acceptability among residents for further Narrative Medicine curriculum, and (2) bolster the findings of similar studies involving internal medicine residency trainees. Residency training was selected as the optimal timing for narrative medicine curricula as this marks a crucial formative period of clinical habit formation for fledgling physicians.

Methods:

An Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained within our institution. As internal medicine residents normally participate in a noon conference and this curriculum was considered to be within the normal scope of educational training a waiver of written consent was obtained. With the permission of the Program Director, the internal medicine residency class was provided details of the upcoming narrative sessions through electronic mail and asked to voluntarily participate. By volunteering to participate in the study and answering the survey questions, the residents provided their consent for involvement in the study. In total, residents rotating through four hospitals of a large, academic internal medicine residency program were invited to the study, with participants in two hospitals serving as the intervention group and the remaining two as the comparison group.

Within the intervention group, the residents participated in four consecutive one-hour weekly narrative medicine workshops during the scheduled hour-long noon conference. Each session was led by a facilitator with Master’s degree training in Narrative Medicine, and consisted of the following: a creative work was introduced to the group followed by facilitated discussion with an emphasis on close examination of the work’s composition. The creative works included a book excerpt, poem, audio recording, and a video, all of which were publicly available and included medical and non-medical topics. This was followed by a brief period of writing to a prompt prepared and provided by the facilitator. Participants were invited to volunteer to read their writing, which was subsequently discussed by the group. Occasionally, participants were prompted to share their writings in pairs prior to larger group discussions to facilitate discussion, in which case participants were informed before prompted writing. The sessions concluded with a brief collective reflection on the participants’ experiences during the session (see Appendix A for a description of the workshop format, creative works that were chosen and prompts that were used).

Due to the previously described scheduling complexities, the residents were included in this study using a convenience sample. Residents in the intervention and control groups completed a pre- and post-survey which queried demographic information, the Interpersonal Reactivity Index, and previous knowledge of Narrative Medicine topics (see Appendices B, C, D, E). Participants completed pre-test survey in-person, on paper, while they completed the post-test survey either in-person or on-line via Survey Monkey. Among the intervention groups, the post-survey included additional items regarding subjective experiences of the workshop and its utility, and self-reported number of workshops attended (Appendix D).

In this study, the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI) survey was chosen for its multidimensional approach to empathy. There are 28 questions within the IRI made up of four constructs, 7 questions apiece measured on a Likert scale. The 4 constructs are operationalized as such (1) perspective taking – or “the tendency to spontaneously adopt the psychological view of others”, (2) fantasy – which looks at respondents’ tendencies to identify with fictional characters, (3) empathic concern – which assesses feelings of warmth, compassion, and concern for others (4) personal distress – which “measures ‘self-oriented’ feelings of personal anxiety and unease in tense interpersonal settings”. [17] Furthermore, unlike other instruments that measure empathy in health care professionals, the IRI is widely available at no cost.

We conducted bivariate analyses to examine the relationship between socio-demographic characteristics of the residents and the group they belonged to, i.e., intervention versus comparison group. Pearson’s chi-squared test was utilized to determine statistical significance. Various subgroup analyses (Spearman correlations) were conducted to identify significant correlations between surveyed resident characteristics and study outcomes. Shapiro Wilk’s test was conducted to test the normality of the data. As the data was not found to be normally distributed, we employed non-parametric tests for the subsequent analyses. Pre and post intervention differences in subscale measures of the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI) for the intervention and control groups were calculated using Wilcoxon Signed Rank test. Various subgroup analyses (Spearman correlations analyses) were conducted to identify significant correlations between surveyed resident characteristics and study outcomes. All statistical analyses were conducted using R version 3∙5∙1 (University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand), R Studio Version 1∙1∙423 (Boston, MA) and Tableau version 2020.1 (Salesforce, Mountain View, CA). The type-I error rate was set at 5%.

Results:

Baseline characteristics

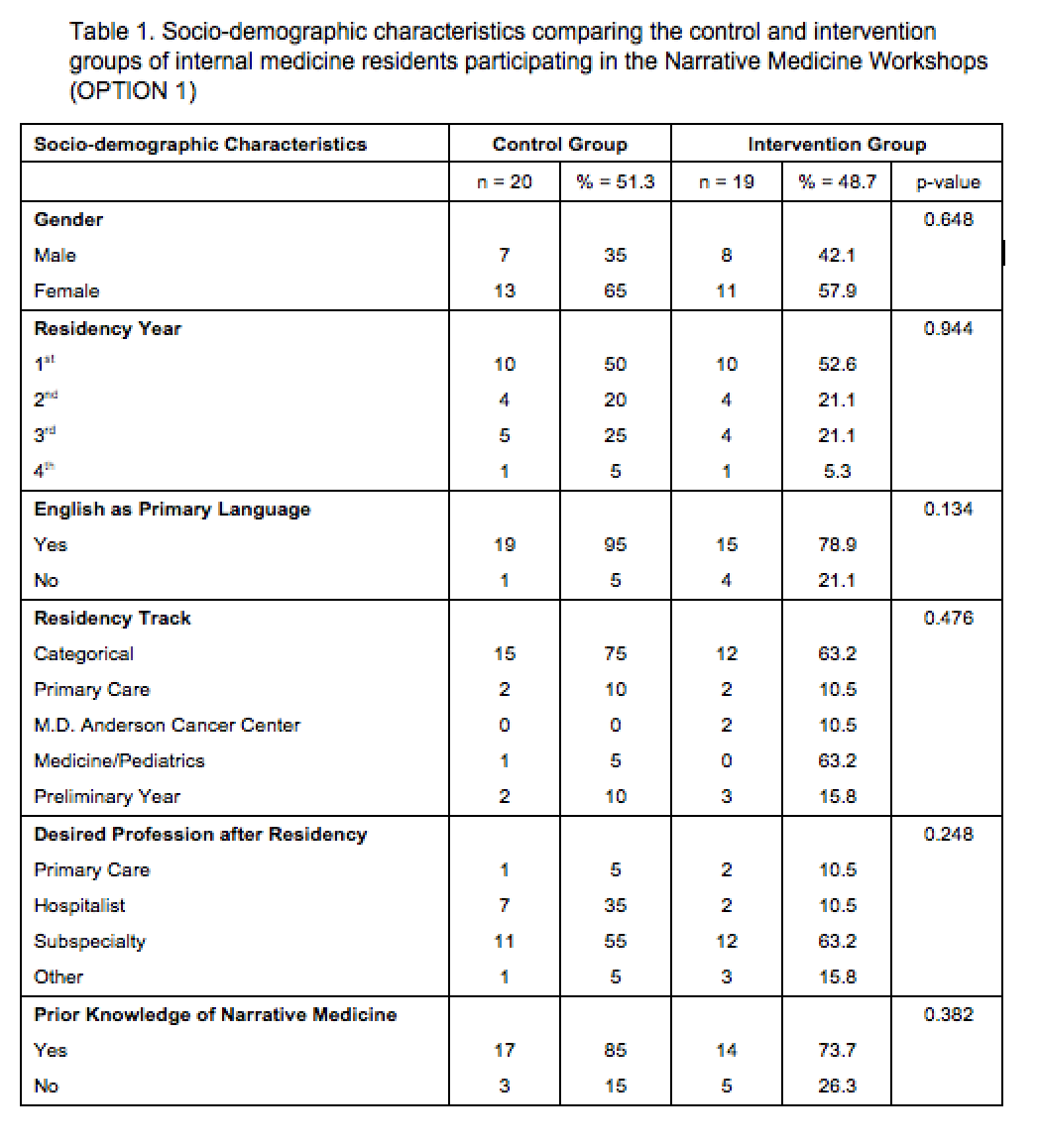

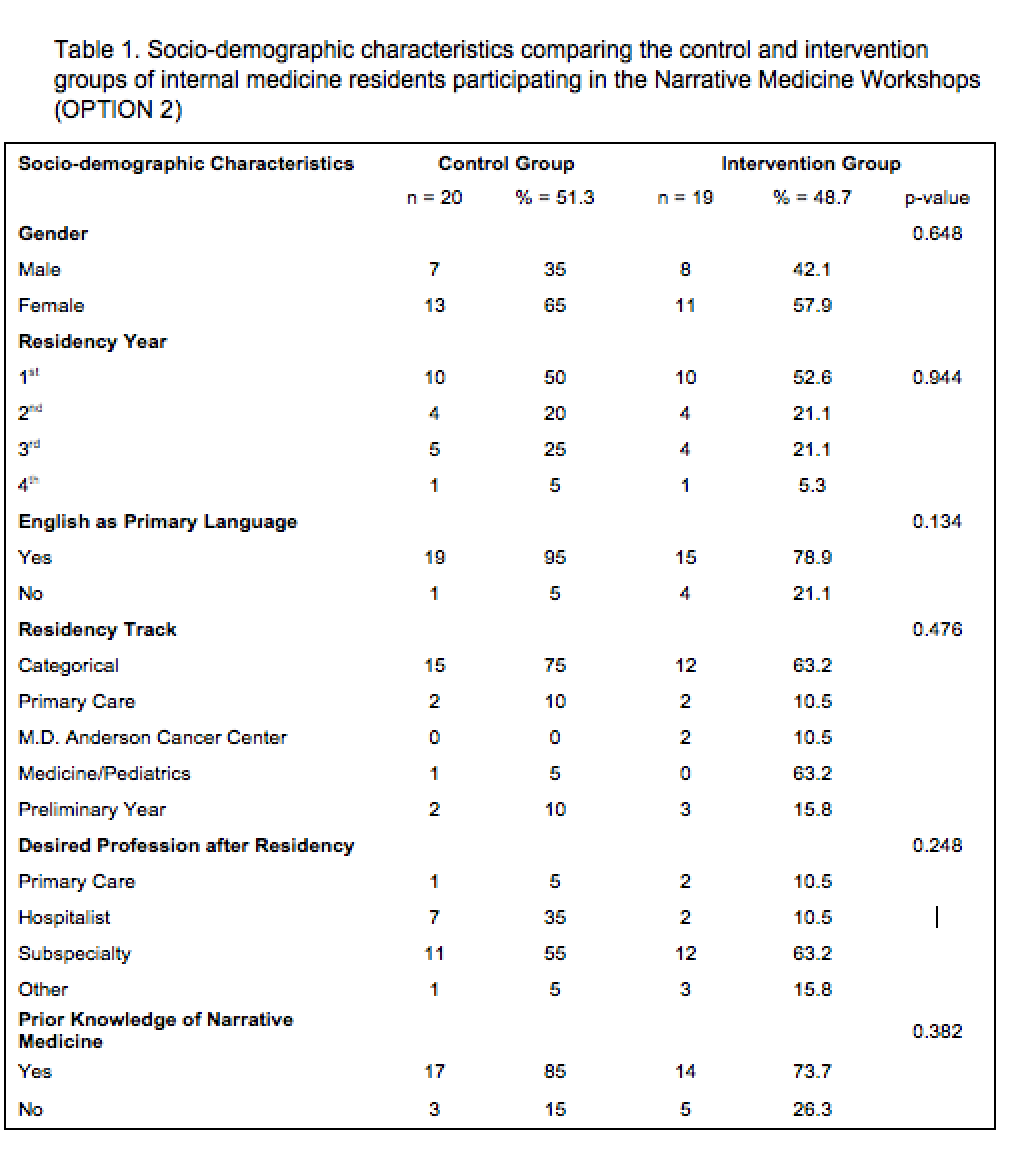

In the control group, 27 individuals completed the pre-survey and 20 completed the post-survey, while in the intervention group, 26 completed the pre-survey and 19 completed the post-survey. Retention rates were nearly identical, with 74.1% in the control group and 73.1% in the intervention group. Baseline characteristics were similar in both groups (table 1). To be included in the analysis, post-surveys were only included when completed by individuals who also completed the pre-survey.

Of those who completed the pre-test survey, chi-squared analysis indicated no statistically significant demographic differences between the comparison group (n=20) and the intervention group (n=19) with regard to gender, English as the primary language, year of residency, specific internal medicine residency track, desired future career, nor prior knowledge of narrative medicine (table 1). While the majority of participants were internal medicine residents, 21% of those who completed the post-test surveys were trainees of other medical specialties attending internal medicine rotations, including residents in preliminary year, anesthesia, neurology, and med/peds.

Intervention participation

Of the residents who participated in the intervention group, 57% attended at least three of the four weekly workshops, with 11% attending just one session. The intervention group consisted of 53% first year residents who were rotating on the internal medicine service.

Acceptability of workshop

In the intervention group post-survey, residents responded to five survey items relating to acceptability of the narrative medicine workshop, specifically their enjoyment of the session (Q1), b) interest in similar workshops in the future (Q2) and c) perceptions of how useful such workshops are to patient care, or in other words, the perceived clinical utility (Q3-5).

In response to the first 2 questions, 70% of residents responded "agree" or "strongly agree" on a 5-item Likert scale to the statement, "I would attend similar workshops in the future," while 73% of residents answered similarly to the statement, "I enjoyed the workshops." Sixty percent of residents indicated the workshops were valuable to patient care, while 50% indicated they could relate better to patients as a result of these sessions; 43% indicated the workshops would improve patient care (figure 1). Of note, there were more neutral responses in questions pertaining to perceived clinical utility of the narrative medicine workshops.

Interpersonal Reactivity Index analysis

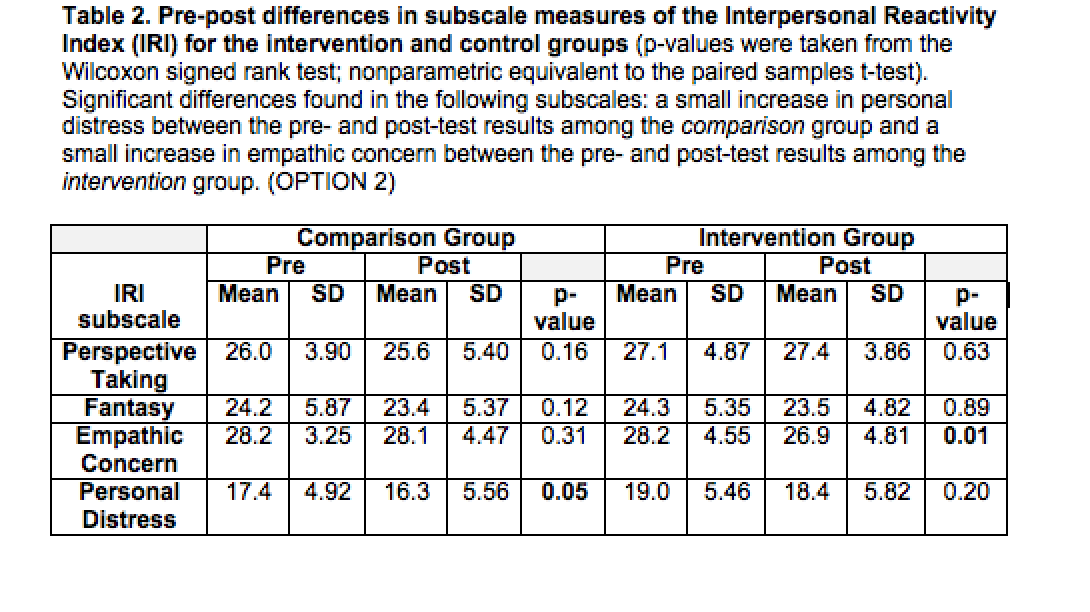

While this study was not statistically powered to identify significant changes in the IRI subscales, statistical comparison of IRI results between the intervention and control groups yielded two significant findings.

Firstly, there was a statistically significant increase in empathic concern (p=0.01, Wilcoxon signed-rank test) between the intervention group as compared with the control group, with statistically insignificant changes in the remaining IRI subscales of perspective-taking, fantasy, and personal distress (table 2). Secondly there was also a significant increase in personal distress noted between the pre- and post- surveys in the control group (p=0.048).

Subgroup analyses

A significant inverse correlation was identified between year of residency and number of sessions attended (p <0.05). There was also a direct relationship between residency year and agreement with the statement, "these workshops will improve my patient care" (p < 0.02). Compared to male residents, female residents were more likely to describe greater acceptability of the workshops (p < 0.05).

Residents a) who described interest in further workshops, b) found the workshops to be valuable or c) indicated their belief that the workshops could improve patient care, scored significantly lower in the personal distress subscale in their post-intervention IRI (p < 0.02, 0.02, and 0.01, for the related questions, respectively).

Also, residents a) who described interest in further workshops, b) found the workshops to be valuable or c) indicated their belief that the workshops could improve patient care, scored significantly lower in the personal distress subscale in their post-intervention IRI (p < 0.02, 0.02, and 0.01, for the related questions, respectively).

Discussion:

Teaching narrative medicine is emerging as an increasingly common practice in professional healthcare education. Previous work has explored the challenges of implementing this approach into practice, demonstrating the short-term benefits of a narrative medicine curriculum during internal medicine resident education and suggesting larger prospective studies to further elicit long-term positive effects [15, 21]. Other studies have demonstrated narrative medicine’s potential effectiveness in improving aspects of clinical care related to key competencies during residency and fellowship training, such as empathy [22, 23, 24]. Our study extends this prior work by including residents from all years of internal medicine training in a large academic program.

Our work demonstrates the acceptability of a narrative medicine curriculum during internal medicine residency among residents in all years of training. A majority of residents regarded the narrative medicine workshop positively in their rating of workshop enjoyment and indicated they would attend similar workshops in the future. Perceived positive implications on clinical practice were more mixed, with a majority indicating the workshops were valuable to their patient care, however only a plurality indicated they could “relate better to my patients as a result of these sessions” and that the workshops would improve their patient care. This was a result of an increase in the number of neutral responses, which may indicate more residents were either unsure of the benefit of the workshops or believed it to have no effect. Despite this increase, few residents believed their participation to negatively impact their clinical care. Particularly notable was the finding that 70% of residents would attend similar workshops in the future, which can be seen as a holistic measure considering both workshop experience and beliefs about its usefulness. Interestingly, participants in the control group demonstrated an increase in personal distress, whereas those in the intervention group did not. This may hint at an increase in personal distress during usual residency training for which this intervention may have been protective. This pilot suggests that structured, sustained exposure to narrative medicine is acceptable to internal medicine residents at this academic internal medicine residency program.

Subgroup analyses identified an inverse correlation between year of residency and the number of workshop sessions attended; interns attended more workshop sessions compared to upper-level residents. It is unclear whether this was a response to the sessions specifically or was consistent with usual conference attendance patterns among internal medicine residents at various stages of training. Interestingly, more experienced residents were more likely to indicate the workshops could improve patient care, despite attending fewer sessions. Considering the well-documented deterioration in empathy during medical school and progression of burnout and disillusionment during residency, perhaps residents in their later years are better positioned to perceive positive implications of this form of narrative training on patient care.

This study also identified gender-specific experiences and outcomes similar to previous studies. In a 2017 study, Chen et. al. [16] found a narrative medicine program to improve empathy, with impacts lasting up to 18 months post-intervention, but with larger and more sustained relative rise among women [16]. Our study also notes a difference between males and female residents, with females scoring a higher acceptability rating of the workshop.

Analysis also indicated improvements in residents’ subscale scores for empathic concern, defined as feelings of warmth, compassion, and concern for others. While modest in impact size, this improvement supports prior literature demonstrating that narrative medicine curricula in graduate and undergraduate medical education may advance ACGME competencies specifically related to communication, collaboration, professionalism, reflective capacity and empathy [22, 25, 26]. If the described increase in empathic concern is valid, several explanatory mechanisms may be at play. Simply providing an hour of non-clinical work during a grueling rotation may itself have positive impacts on resident well-being, burnout, and thus conceivably, capacity for empathy. Furthermore, a physician’s capacity for empathy towards their patients relies on a physician’s own emotional well-being as they face daily challenges in medicine, which can result in compassion fatigue, burnout, and a low sense of accomplishment [27]. Additionally, in this study, residents were asked to participate in a number of reflective writing exercises, which itself has been linked to effects on medical students' empathy during the undergraduate medical curriculum, which may apply to postgraduate trainees [28].

This empathic concern, if persistent in larger-scale studies, can hold significant implications for clinical care. General practice physicians with both high empathic concern and high perspective-taking scores have experienced less burnout than their counterparts [29]. Furthermore, physician empathy can affect patient outcomes in satisfaction, treatment adherence, enablement, and psychological distress [30]. Thus, graduate medical education programs that incorporate Narrative Medicine into their longitudinal curriculum may have the potential to achieve similar effects and reduce resident burnout, promote resident well-being, and improve patient care, though this would require extensive further study.

There were several limitations to this study. Due to the very small sample size this study is not powered for robust statistical analyses. Only 20% of the approximately 180 total residents in this residency program were included in this study, limiting its generalizability. Secondly, while narrative medicine workshops are typically conducted with between eight to ten participants per workshop to facilitate individual participation and the inclusion of diverse opinions, the workshops in this study included between 13 and 20 participants per session. Also, it is unclear whether the frequency and number of workshops attended constituted sufficient didactic exposure for adequate skill development. Further studies could explore a schedule of workshops held more frequently than once per week, for a greater duration, or perhaps with a commitment from participants to a minimum number of sessions. Lastly, the intervention groups were rotating through busy tertiary and quaternary hospital settings of the residency program. As documented previously, their demanding clinical schedule may have led them to participate in fewer workshops, limiting their skill development.

Despite these limitations, this pilot study confirmed its primary intent to assess the acceptability of a noon conference narrative medicine workshop curriculum in a large academic internal medicine residency training program, with a majority of residents who participated in more than half of sessions indicating they enjoyed the workshops, believed it contributed to their clinical care, and indicated an interest to attend similar workshops in the future. Interpersonal Reactivity Index survey analysis demonstrated improvement in a form of empathy known as empathic concern, which has been inversely correlated with clinical burnout in general practitioners. This demonstrates promise for the use of similar narrative medicine workshop interventions within internal medicine residency program curricula in the future, though this warrants confirmation in further research. This perceived benefit among residents suggests similar workshops are acceptable and effective tools to address aspects of ACGME core competencies such as interpersonal and communication skills and professionalism. Furthermore, including narrative medicine in medical training curricula to develop the skills of close listening and reflective writing early in a physician's formative training may facilitate adoption of these skills into clinical practice throughout the lifetime of the clinician.

In conclusion, this pilot study demonstrates the acceptability of a narrative medicine curriculum incorporated into a regular noon conference schedule among Internal Medicine residents, and may encourage the continued inclusion of Narrative Medicine workshops in noon conference curricula. Future studies with greater workshop exposure, and instruments that measure additional aspects of clinical well-being such as burnout are specifically needed to better elucidate the impacts of narrative medicine on the lived experience of physician training. Furthermore, semi-structured interviews with qualitative analysis may better explore the individual cognitive experience of participation in narrative medicine workshops. Further down the road, clinical outcomes in chronic disease, physicians’ experience of care, and rates of burnout offer enticing downstream targets for further investigation. While more longitudinal studies are needed to examine the long-term impact of narrative medicine on burnout among physicians, developing the skills to take time to sit and receive the routine accounts that our patients offer to us can benefit both patients and physicians. While most traditional internal medicine residency programs invariably address the pathophysiology of disease and the treatment of these ailments, perhaps the time has come to provide fledgling physicians an opportunity to practice the art of medicine.

Funding statement

This research was supported by grant number 1 D34HP31024-01-00 from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) for the project titled Baylor College of Medicine (BCM) Center of Excellence in Health Equity, Training & Research. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of BCM, HRSA, or the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Declaration of Interest:

None of the authors report any conflict of interest.

References

1. Joyner, Byron D. “An historical review of graduate medical education and a protocol of Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education compliance.” The Journal of urology vol. 172,1 (2004): 34-9. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000121804.51403.ef

2. Marple, Bradley F. “Competency-based resident education.” Otolaryngologic clinics of North America vol. 40,6 (2007): 1215-25, vi-vii. doi:10.1016/j.otc.2007.07.003

3. Charon, R. “The patient-physician relationship. Narrative medicine: a model for empathy, reflection, profession, and trust.” JAMA vol. 286,15 (2001): 1897-902. doi:10.1001/jama.286.15.1897

4. Charon, R. Narrative Medicine: Attention, Representation, Affiliation. Narrative. 2005;13(3): 261-270. DOI:10.1353/nar.2005.0017

5. Neumann, Melanie et al. “Physician empathy: definition, outcome-relevance and its measurement in patient care and medical education.” GMS Zeitschrift fur medizinische Ausbildung vol. 29,1 (2012): Doc11. doi:10.3205/zma000781

6. Bellini, Lisa M, and Judy A Shea. “Mood change and empathy decline persist during three years of internal medicine training.” Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges vol. 80,2 (2005): 164-7. doi:10.1097/00001888-200502000-00013

7. Foreback, Jami et al. “Empathy in Internal Medicine Residents at Community-based Hospitals: A Cross-sectional Study.” Journal of medical education and curricular development vol. 5 2382120518771352. 30 Apr. 2018, doi:10.1177/2382120518771352

8. McFarland, Daniel C et al. “Acute empathy decline among resident physician trainees on a hematology-oncology ward: an exploratory analysis of house staff empathy, distress, and patient death exposure.” Psycho-oncology vol. 26,5 (2017): 698-703. doi:10.1002/pon.4069

9. Paro, Helena B M S et al. “Empathy among medical students: is there a relation with quality of life and burnout?.” PloS one vol. 9,4 e94133. 4 Apr. 2014, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0094133

10. Charon, Rita et al. “Close Reading and Creative Writing in Clinical Education: Teaching Attention, Representation, and Affiliation.” Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges vol. 91,3 (2016): 345-50. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000827

11. Liao, Joshua M, and Brian J Secemsky. “The Value of Narrative Medical Writing in Internal Medicine Residency.” Journal of general internal medicine vol. 30,11 (2015): 1707-10. doi:10.1007/s11606-015-3460-x

12. Gowda, Deepthiman et al. “Implementing an interprofessional narrative medicine program in academic clinics: Feasibility and program evaluation.” Perspectives on medical education vol. 8,1 (2019): 52-59. doi:10.1007/s40037-019-0497-2

13. Miller, Eliza et al. “Sounding narrative medicine: studying students' professional identity development at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons.” Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges vol. 89,2 (2014): 335-42. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000098

14. Gaufberg, Elizabeth H et al. “The hidden curriculum: what can we learn from third-year medical student narrative reflections?.” Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges vol. 85,11 (2010): 1709-16. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181f57899

15. Wesley, Tiffany et al. “Implementing a Narrative Medicine Curriculum During the Internship Year: An Internal Medicine Residency Program Experience.” The Permanente journal vol. 22 (2018): 17-187. doi:10.7812/TPP/17-187

16. Chen, Po-Jui et al. “Impact of a narrative medicine programme on healthcare providers' empathy scores over time.” BMC medical education vol. 17,1 108. 5 Jul. 2017, doi:10.1186/s12909-017-0952-x

17. Davis, M.H. A Multidimensional Approach to Individual Differences in Empathy [dissertation on the Internet]. Ann Arbor, Mich: UMI Dissertation Services; 1980 [cited 2021 Feb 10]. Available from: https://www.uv.es/~friasnav/Davis_1980.pdf

18. Lucas-Molina, Beatriz et al. “Dimensional structure and measurement invariance of the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI) across gender.” Psicothema vol. 29,4 (2017): 590-595. doi:10.7334/psicothema2017.19

19. de Lima, Felipe Fernandes, and Flávia de Lima Osório. “Empathy: Assessment Instruments and Psychometric Quality - A Systematic Literature Review With a Meta-Analysis of the Past Ten Years.” Frontiers in psychology vol. 12 781346. 24 Nov. 2021, doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.781346

20. Hojat, Mohammadreza et al. “Relationships between scores of the Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy (JSPE) and the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI).” Medical teacher vol. 27,7 (2005): 625-8. doi:10.1080/01421590500069744

21. Zazulak, Joyce et al. “The art of medicine: arts-based training in observation and mindfulness for fostering the empathic response in medical residents.” Medical humanities vol. 43,3 (2017): 192-198. doi:10.1136/medhum-2016-011180

22. Arntfield, Shannon L et al. “Narrative medicine as a means of training medical students toward residency competencies.” Patient education and counseling vol. 91,3 (2013): 280-6. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2013.01.014

23. Harrison, Madaline B, and Nicole Chiota-McCollum. “Education Research: An arts-based curriculum for neurology residents.” Neurology vol. 92,8 (2019): e879-e883. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000006961

24. Shaw, Andrew C et al. “Integrating Storytelling into a Communication Skills Teaching Program for Medical Oncology Fellows.” Journal of cancer education : the official journal of the American Association for Cancer Education vol. 34,6 (2019): 1198-1203. doi:10.1007/s13187-018-1428-3

25. Wald, Hedy S, and Shmuel P Reis. “Beyond the margins: reflective writing and development of reflective capacity in medical education.” Journal of general internal medicine vol. 25,7 (2010): 746-9. doi:10.1007/s11606-010-1347-4

26. Davidson, John H. “Clinical empathy and narrative competence: the relevance of reading talmudic legends as literary fiction.” Rambam Maimonides medical journal vol. 6,2 e0014. 29 Apr. 2015, doi:10.5041/RMMJ.10198

27. Gleichgerrcht, Ezequiel, and Jean Decety. “Empathy in clinical practice: how individual dispositions, gender, and experience moderate empathic concern, burnout, and emotional distress in physicians.” PloS one vol. 8,4 e61526. 19 Apr. 2013, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0061526

28. Chen, Isabel, and Connor Forbes. “Reflective writing and its impact on empathy in medical education: systematic review.” Journal of educational evaluation for health professions vol. 11 20. 16 Aug. 2014, doi:10.3352/jeehp.2014.11.20

29. Lamothe, Martin et al. “To be or not to be empathic: the combined role of empathic concern and perspective taking in understanding burnout in general practice.” BMC family practice vol. 15 15. 23 Jan. 2014, doi:10.1186/1471-2296-15-15

30. Johnson Shen, Megan et al. “Structured Analysis of Empathic Opportunities and Physician Responses during Lung Cancer Patient-Physician Consultations.” Journal of health communication vol. 24,9 (2019): 711-718. doi:10.1080/10810730.2019.1665757

Faiz Jiwani is a community physician currently partnering with patients at Legacy Community Health, an FQHC located primarily in Houston, Texas. He holds a Master's degree in Narrative Medicine and has conducted narrative medicine workshop series with medical students, residents, medical school faculty and community social workers. He has contributed to undergraduate medical education in the areas of social determinants of health, implicit bias training and narrative medicine. In his clinical practice, he derives particular fulfillment from improving medical care for patients who are underhoused and/or justice-involved.

Rebecca A. Rosero is a scholar of the Baylor College of Medicine, Center of Excellence, Transformed Post-Baccalaureate Premedical program and holds a bachelor's degree in Biology from the University of St. Thomas. Her interests in Narrative Medicine stem from the fulfillment she attains through helping the marginalized and overlooked receive medical care. By continuously participating in research and medical missions both globally and within Houston, she has seen the personal and community impact that medical care can have on patients affected by health inequity and desires to contribute to the advancements toward bettering healthcare for all patients.

Deepa Dongarwar is a data scientist at the Department of Neurology at University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston’s McGovern Medical School. She is passionate about research in the field of health disparities, women’s health and incorporating data science techniques in the field of epidemiologic research. She continues to mentor undergraduate, medical and post-doctoral students, clinical fellows and faculty in the field of biostatistics and clinical research methods.

Larry Laufman, EdD, is an Associate Professor in the Department of Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine. With a doctorate in Foundations of Education from the University of Houston, his work has included medical and health education research, demonstration and program evaluation projects targeting patients and their families, medical students, physicians and other healthcare professionals. Having worked for 25 years on projects to reduce health disparities for minority and underserved communities, he works with clinicians who care for adult patients with lifelong disabilities in Baylor’s Transition Medicine Clinic. He is a small group discussion leader in Baylor’s medical ethics course; and he conducts program evaluation for the Humanities Expression and Arts Lab.

R. Michelle Schmidt has been a practicing internist at Baylor College of Medicine within the Harris Health System, a healthcare system for the under and uninsured, for the past 27 years. In addition to her clinical roles, Dr. Schmidt also serves as an advisor to first through fourth year medical students at Baylor College of Medicine and participates as a facilitator in the Narrative Medicine curriculum for the clinical medical students. She is passionate about caring for patients and educating and mentoring learners. Teaching and mentoring have allowed her to be a better physician as she implements these same skills in my patient encounters. By listening to patients and their families as they share their stories, she has become a more attentive teacher.