“A schizophrenic is no longer a schizophrenic…when he feels understood by someone else” reads the epigraph on this quietly powerful book of poetry by pediatric nurse practitioner Katherine DiBella Seluja. The words come from Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Carl G. Jung and introduce the reader to the emotional heart of the book, which movingly reflects the facets of the writer’s life, as a clinician, poet and understanding sister to a brother named Lou who lived with schizophrenia and substance addiction.

The slim volume, published by the University of New Mexico Press, is divided into four sections: Time Travel; Free Concert; Sing to Me; and Stars Speak. Each section starts with a short free-form prose poem in an imagined voice, perhaps that of Lou’s, drawing a vivid visual tableau. In terms of overall structure, the book has a narrative arc that spans from childhood through adulthood, from beginnings to endings. Some poems are tales of families and communities dealing with mental illness in everyday life and in startling moments of illness and death. Throughout, Seluja, whose poem about Parkinson’s, “Not Every Homemade Thing,” appeared in our Spring 2017 issue, brings her vivid language, compassionate affection, deeply-felt visions and clinical observations into poems that transport readers close to the tragedies and the moments of inspiration, as well as the experience of grief and acceptance, as she receives and perceives them.

One of the most original and skillful aspects of this collection is that we hear more than the poet’s voice on these pages: Seluja has said that Gather the Night includes “prose poems and persona poems that express the voice of psychosis, the voice of addiction and Lou’s imagined voice.” While each poem stands solidly on its own, reading from beginning to end increases the intensity of the connection with the people, places and things in it. In Time Travel, for instance, we see neighborhoods and neighbors, some sly and seductive (Reynaldo in “Chiquita”) and some down-to-earth and welcoming (Scottie, the grocer and Mrs. Gratzel, the baker’s wife in “Local Grown.”). We see the pummeling a sister gets from a brother in the name of karate practice in “Kata,” or the way a mother delivers bad news in “Storm Hymn”:

One thin crack in the plastic sign

on the locked ward door

Winds its way through

Authorized Personnel Only

like a branch of the Hackensack River

where we used to play.

Dried mud thick on our shoes

split in so many places,

our mother’s face when she said,

We just admitted your brother;

he told us his crystals were melting.

Waiting for the orderly to turn his key

I turn back to our winter childhood refuge

under the cellar stairs.

We were base camp

guardians of snow

charted drift and temperature

graphed hope for Sunday night storms.

Now gray clouds

and Thorazine doses increase,

he wanders the blizzard alone

no guide rope tied to the door,

unique as each stellar dendrite

no two of him alike.

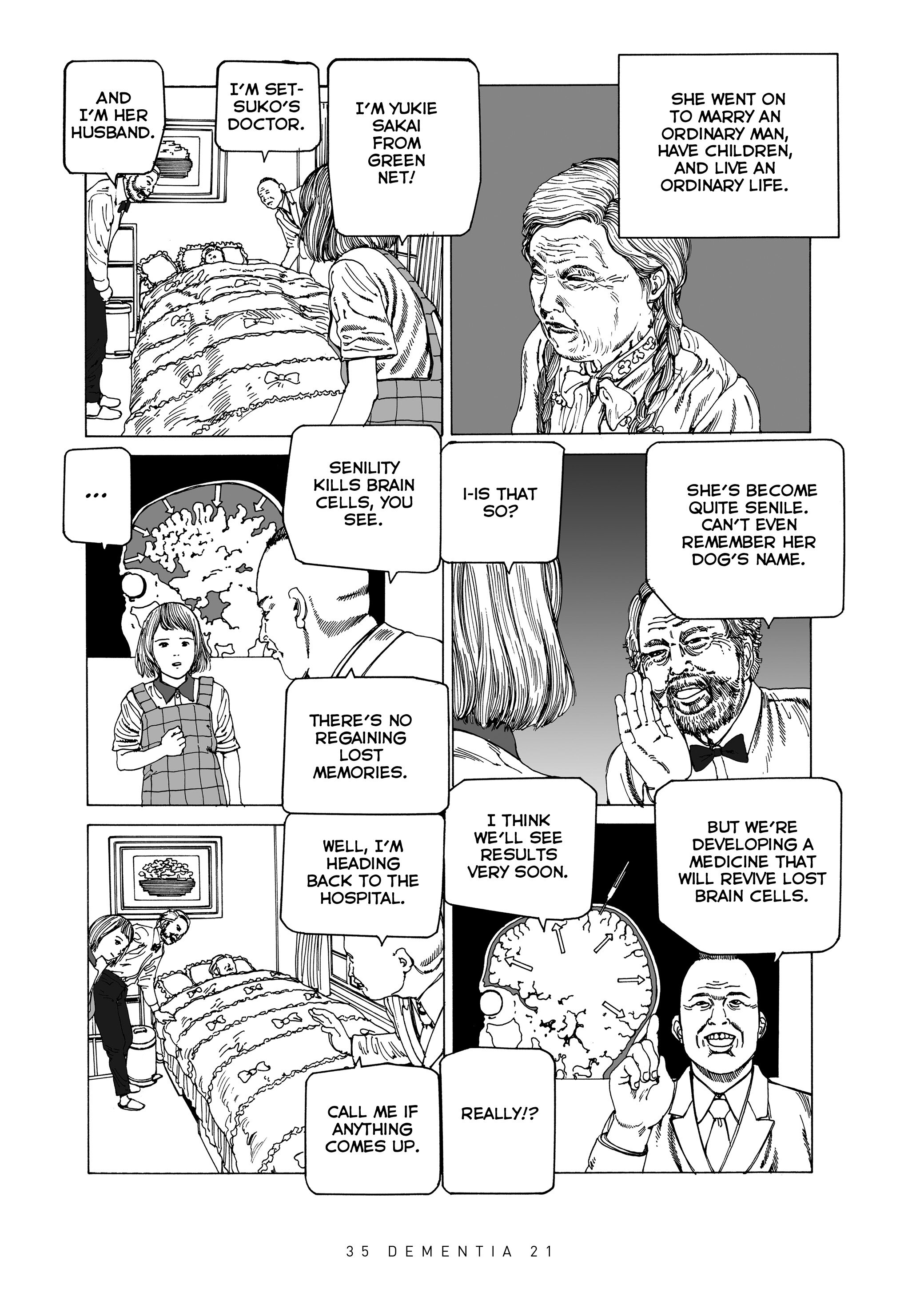

Along with the concrete, graceful imagery of the poems, we also receive information about illness and madness—and how the clinical world handles it, especially in the second section, Free Concert. We hear from a doctor in “The Psychiatrist Said” (“It’s [the schizophrenia] all a matter of proteins/We’ll have it cracked in three to four years”), while we glimpse inside a medical facility in “Spinning with Thorazine.” We witness Seluja’s ambitious way of contemplating and confronting the big-picture issues of care in poems such as the ironic “The History of Healing” (“It began as a huddle of knowers, passed through oral tradition/those who could ‘heal’ and those who at least attempted”). The chilling “When Your Son is Diagnosed in the 1960s” notes an earlier era’s method of treatment and causes (“His psychosis is tied to your mothering/and it’s time to cut the chord, be careful of the sting”).