TOWARDS BIOPSYCHOSOCIAL APPROACHES IN HEALTHCARE:

Postgraduate Dentistry Students’ Experience of Transformative Education | Homa Fathi

Authors: Homa Fathi (1*), Anahita Ranjbar (2), Richard Hovey (1,) Christophe Bedos (1).

1. Faculty of Dental Medicine and Oral Health Sciences, McGill University, Montreal, Canada

2. General Dentist, Kashan, Iran.

Abstract

Dentistry has traditionally been shaped by the biomedical model, fostering a reductionist focus on pathology and technical intervention while neglecting patients’ psychosocial realities. To encourage a more holistic approach, McGill Faculty of Dental Medicine and Oral Health Sciences created a two-credit course based on the Montreal-Toulouse Model (MTM), an innovative biopsychosocial framework. Grounded in Transformative Learning Theory, this course used narratives such as comics and vignettes to support students’ learning. We conducted a qualitative descriptive study to explore the experiences of eight postgraduate dentistry students registered in the course through individual and group interviews. Thematic analysis revealed that all participants experienced some degree of transformation in their perception of biopsychosocial approaches, especially regarding community action and advocacy. Narratives facilitated empathy and understanding of how social structures shape health, while feelings of safety and inclusion were essential for enabling critical reflection. Our findings suggest that narrative-based transformative learning can help health care students adopt biopsychosocial approaches, preparing them for more humanistic and socially responsive practice. However, students used to passive learning may struggle with independent thinking, questioning norms, or handling creative tasks. Educators should expect these challenges and provide support as students adapt to new learning methods.

Keywords: biopsychosocial approaches; transformative learning theory; dental education; comics; vignettes.

Introduction

The biopsychosocial model emerged in the late 20th century to address the biomedical model’s limitations, which defined disease as isolated biological dysfunction and often overlooked patients’ psychological states and social contexts (Engel). In dentistry, this reductionist focus on pathology and technical intervention has largely neglected patients’ psychosocial realities, proving inadequate for managing chronic oral conditions and contributing to poor communication, patient dissatisfaction, and clinician burnout. (Apelian et al.).

Recognizing these shortcomings, the World Dental Federation and the World Health Organization have called for a broader orientation that addresses the full spectrum of patient needs, not merely symptoms (Berge et al., Glick and Williams, World Health Organization). Biopsychosocial approaches align with this vision by re-centering dentistry within a humanistic, socially conscious practice that values patients’ lived experiences and the social determinants shaping their health (Bedos et al. "Social Dentistry", Bedos et al. "Towards a Biopsychosocial Approach").

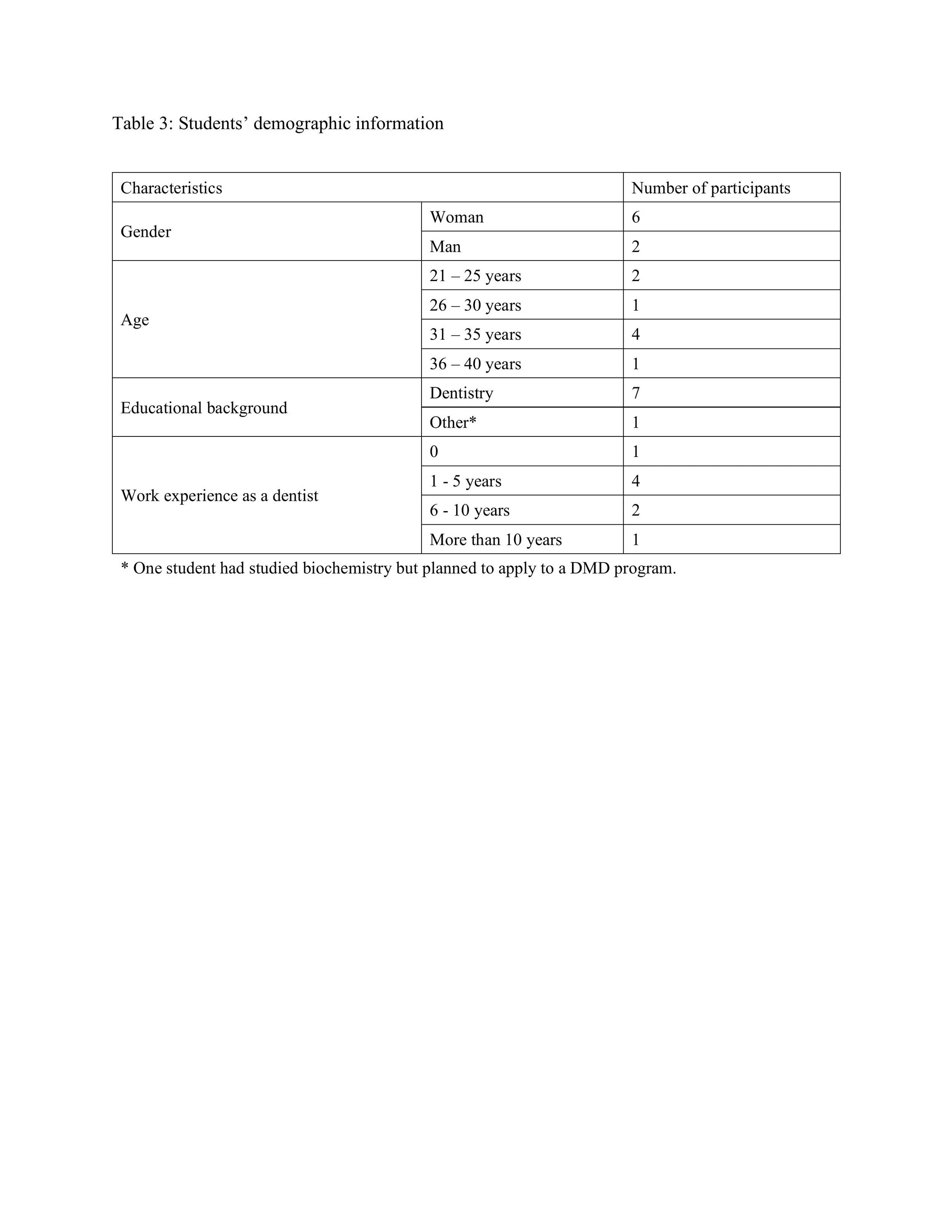

One such approach is the Montreal–Toulouse Model (MTM): introduced to the literature in 2020, it represents a continuation of Bedos et al.’s work in advancing biopsychosocial approaches in dentistry, integrating the core values of person-centered care and social dentistry into a cohesive framework (Bedos et al. "Towards a Biopsychosocial Approach"). The MTM guides dentists to take three types of action – understanding, decision-making, and intervening – across three interconnected levels: individual, community, and societal (see Figure 1). At the individual level, it promotes person-centered care; at the community level, it encourages adapting practices to local needs and collaborating with communities; and at the societal level, it advocates for systemic change by addressing social, political, and economic factors.

Teaching biopsychosocial models like the MTM in dental schools supports the shift toward more holistic education. However, traditional methods that position students as passive recipients may be insufficient to challenge entrenched practices (Kumagai). Scholars therefore advocate for transformative learning strategies – such as using narrative literature and art, and reflexive writing – that foster critical consciousness and reflexivity (Asa'ad, Charon). Like narrative medicine, the MTM holds that patient care is enriched when clinicians engage deeply with patients’ lived experiences, values, and contexts (Charon). While narrative medicine cultivates interpretive and reflective skills to honor patient stories, the MTM extends these principles by embedding them within a structured framework that combines reflection with concrete biopsychosocial action, advocacy, and structural change.

Building on these principles, McGill Faculty of Dental Medicine and Oral Health Sciences developed a two-credit graduate course based on the MTM, aiming to train students in biopsychosocial approaches. Grounded in transformative learning theory, the course consisted of 13 virtual Zoom sessions where students and their professor explored selected narratives – including comic books and vignettes – aligned with the course objectives. Additionally, students wrote weekly reflections and completed a short comic project as their final assignment. To the best of our knowledge, this was the only course at McGill at the time explicitly based on the MTM, while also drawing on the pedagogical principles of Narrative Medicine to support students’ reflective and interpretive learning.

This course offered a unique opportunity to explore how narratives within a transformative learning context could help postgraduate dentistry students adopt the MTM. Accordingly, this study aimed to achieve two objectives: 1) to understand how these innovative teaching methods influence students' learning processes regarding biopsychosocial approaches, and 2) to examine how the course might impact students' professional identity and their vision of dentistry.

Materials and Methods

Ethics approval

This study was conducted in accordance with McGill faculty of medicine's Institutional Review Board (IRB) under the review number (A05-B46-21B (21-05-039)). All students read and signed a written informed consent before participating in the study.

Design and study population

We employed a qualitative descriptive methodology. This approach was well suited to our study because it offers a close-to-the-data account of participants’ experiences in their own everyday terms, staying faithful to their words and meanings without imposing heavy theoretical or abstract interpretations (Sandelowski). The study population consisted of postgraduate dentistry students who enrolled in and completed the course.

Theoretical framework

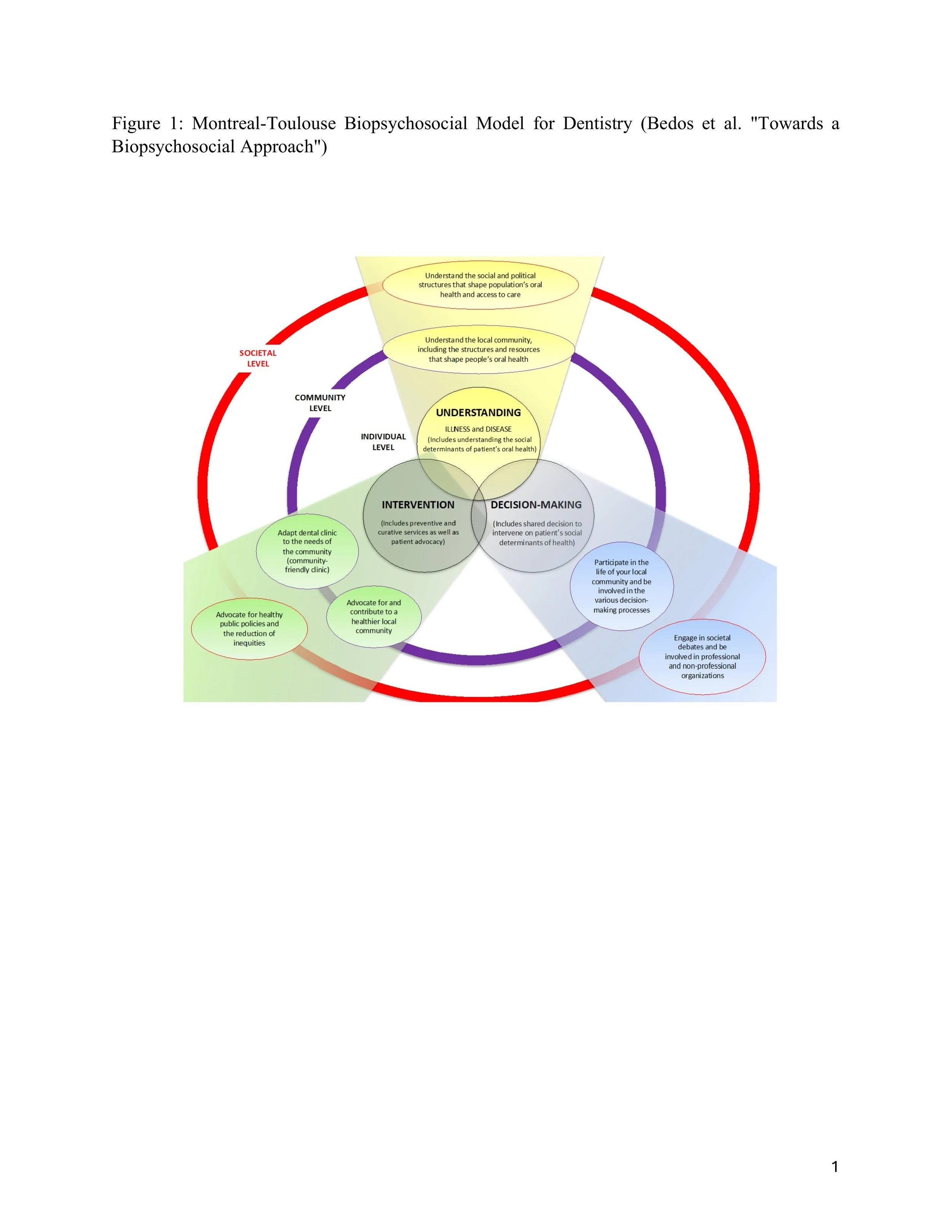

We adopted Mezirow’s transformative learning theory as our guiding framework to understand students’ learning process (Figure 2) (Mezirow, Cranton, Taylor). This theory explains how adults can fundamentally shift their “meaning perspectives” – the assumptions they use to interpret new experiences – through critical reflection and the testing of these perspectives against new evidence. Such transformation often occurs when learners recognize the limitations of their existing perspectives and seek more inclusive, integrative ways of understanding. Because the course aimed to foster critical self-reflection, challenge entrenched assumptions in dental practice, and promote more socially responsive and patient-centered care, transformative learning theory offered the most fitting framework to achieve these objectives.

The course design

The instructor mainly relied on two methods:

1. Reading comics: Students were invited to read comics — graphic narratives in which images complement and enhance a text (Czerwiec) – depicting illness experiences and social determinants of health, often through biographical stories about challenges like discrimination, addiction, and unemployment (Table 1). These selections were pedagogically aligned with the course’s learning objectives, which aimed to foster critical reflection and empathy in clinical contexts.

2. Reading vignettes: The instructor also used vignettes – written narratives of people’s lived experiences (Bernabeo et al. "Utility of Vignettes") – depicting issues similar to those in the comics, and asked students to propose dental interventions addressing social determinants of health. These concise, scenario-based prompts encouraged focused discussion and application of course concepts to realistic clinical situations. Some were drawn from Bedos et al.’s work on social dentistry as a biopsychosocial practice (Bedos et al. "Social Dentistry").

In addition, the instructor gave brief oral presentations and led group discussions. Students kept weekly logs to critically reflect on their assumptions about the topics covered, and for the final assignment, created a short comic aligned with the course objectives.

The instructor had longstanding engagement with graphic medicine, including presenting at the international Graphic Medicine Conference, publishing on using narratives in dentistry, and producing multiple comics – on topics such as poverty and access to dental care – in collaboration with recognized artists, community groups, and public health researchers (RSBO Art and Science Project, Vergnes et al.).

Sampling and data collection

After final marks were released, all eight students agreed to participate in the study and provided written consent approved by McGill’s IRB. One author (Anonymized) conducted one-hour, semi-structured Zoom interviews using an open-ended guide (sample questions in Table 2) to explore students’ experiences. Following the interviews and initial analysis, students joined a one-hour focus group moderated by (Anonymized), with the second author (Anonymized) taking notes and participating in the debriefing. The focus group was used to validate and expand upon themes identified in the individual interviews.

Data analysis

We audio-recorded and transcribed the individual and focus group interviews verbatim. Using MaxQDA software, we analyzed the transcripts through a combination of deductive coding – based on transformative learning concepts (Mezirow) – and inductive coding – detecting themes from the data itself (Green and Thorogood). We collaborated through debriefing sessions to refine themes and prepare for subsequent interviews. During the focus group, we validated the themes by seeking participants' feedback. To ensure trustworthiness, we included numerous anonymized quotations in the results section (Creswell and Miller).

Results

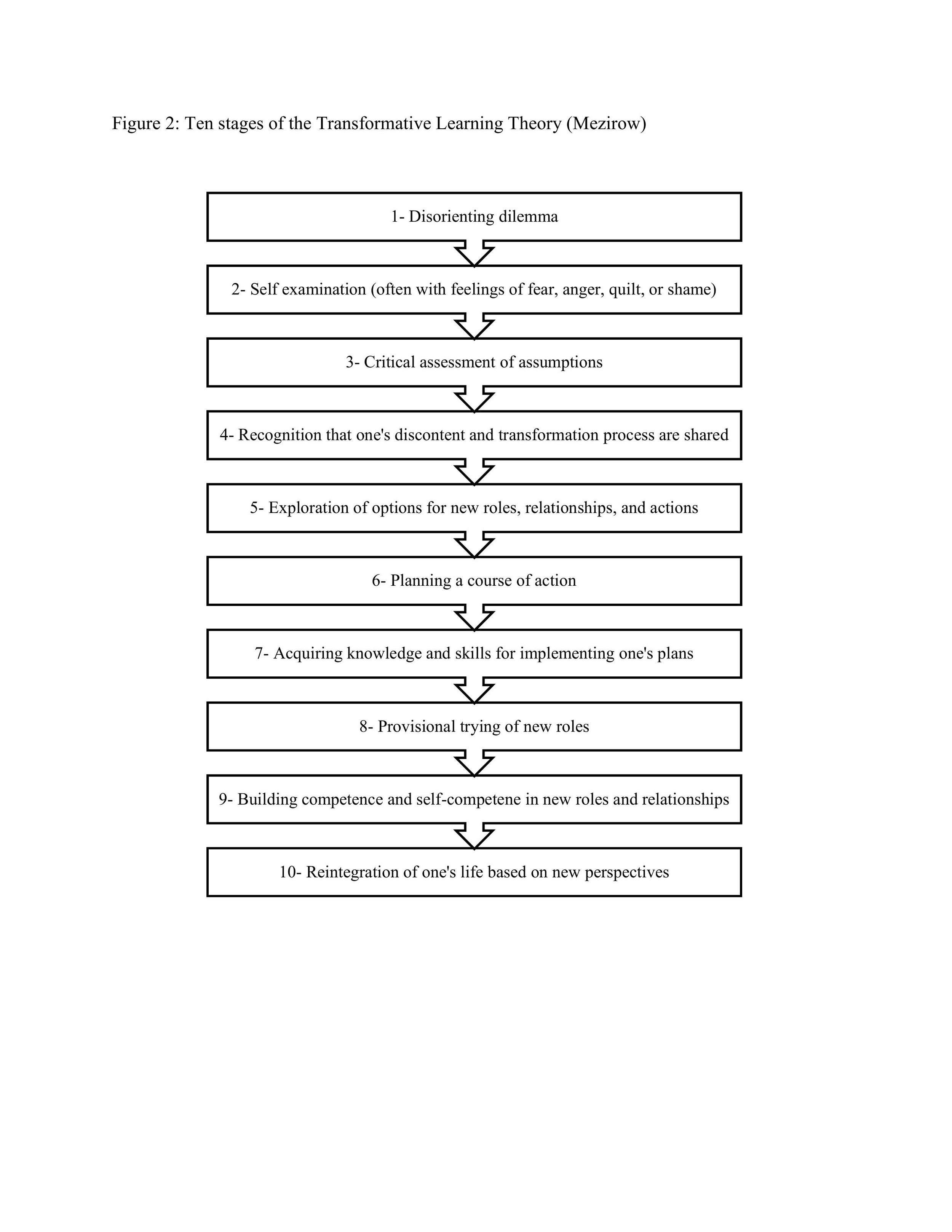

All eight students registered in the course accepted to participate, even though one missed the focus group due to scheduling conflicts. As table 3 shows, most students were women with a dental degree obtained in a different country. Although we cannot reveal their origins for confidentiality reasons, students had practiced dentistry in four different countries. Only one student was not a dentist but planned to apply to a DMD program.

Three main themes emerged from the analysis: 1. Students experienced various degrees of a positive transformation in their perception of the MTM; 2- Narratives facilitated students’ adoption of the MTM; and 3- Feelings of safety and inclusion were fundamental for students’ transformative learning processes.

1. Students experienced various degrees of a positive transformation in their perception of the MTM

All students reported experiencing a transformation during the course and acknowledged their empathy level towards underprivileged people had improved. Sensitized to the MTM and its underlying concepts, they felt enabled to better communicate and address people's needs holistically, including through addressing social determinants of health.

The extent of their transformation nevertheless varied among the participants. On one side, some still favored the biomedical approach, arguing that biopsychosocial methods may not be sustainable in a profit-driven system, where activities like social prescription or advocacy are not remunerated. Others, however, seemed ready to adopt a biopsychosocial approach, emphasizing the importance of improving relationships with underprivileged people, addressing their social determinants of health, and advocating for their rights. Their revised vision of professionalism was rooted in holism and humanism, with some even eager to shift their career paths towards more socially oriented roles.

I have become more empathetic towards [underprivileged] patients. I now give them preference over other patients even if they came late […] (However) you can't just define professionalism based on these approaches…You know, I can't say a person who has taken a loan to open his clinic and has to pay it back is not professional because he does not spend this much time for each patient, or you know, if he's having paternalistic approach. (Student 4)

2. Narratives facilitated students’ adoption of the MTM

Participants considered the course’s pedagogical materials – particularly comics and vignettes – effective educational tools that made the MTM tangible and helped them internalize its core concepts. In addition to these materials, various instructional and assessment methods such as reflective logs, class discussions, and a creative assignment further supported their learning and transformation, as detailed below.

2.1. Pedagogical materials: comics and vignettes

2.1.1. Comics

Comics seemed to have enhanced students’ understanding of the core concepts of the MTM, such as the social determinants of health, social prescription, and health advocacy. Although they had already been introduced to these concepts, they acknowledged their understanding had remained superficial and abstract. Reading comics helped them grasp the complex pathways through which the social context affects health, but also identify ways to address them.

You can teach about the social determinants of health and that logically they affect your oral health, but once you see it in real life in a story, once you have examples, a real example, it will be more powerful to really establish the belief that you need to change social determinants of health in order to have better oral health. (Student 1)

Students highlighted the power of graphic illustrations in understanding people's experiences of illness and suffering. They found comic books to be an engaging, quick, and easy-to-understand medium for learning about highly complex phenomena. The drawings, particularly body expressions and life contexts helped them empathize with diverse characters and better understand harsh realities like illness, poverty, and discrimination.

I believe a picture can express 1000 words. So, it's faster to be completely honest and more entertaining, than just reading those 1000 words… I feel things that probably wouldn't be expressed really well in text, would be better [expressed] via image even if it's really hard-hitting images. (Student 3)

2.1.2. Vignettes

Students considered vignettes essential learning tools as they illustrated clinical encounters relevant to dentistry. Vignettes helped them apply their knowledge and think creatively about addressing patients' social determinants of health. They enabled students to envision themselves in clinicians' roles and explore new professional responsibilities. Discussing vignettes in small groups provided a safe space for collaboration and sharing perspectives, allowing students to learn from each other and broaden their worldviews, especially given their diverse backgrounds and health systems.

When we were working on those vignettes, we could actually think “OK, this same situation can someday happen with me. How would I deal with it?” And then you know the actions you would take at every level, which you would never think about when you were discussing comics. (Student 2)

2.2. Methods of instruction and assessment

2.2.1. Personal logs

Although the personal logs were not part of the pedagogical materials themselves, they served as an instructional and assessment method that supported students’ reflection on the comics and vignettes. Writing weekly logs enabled participants to critically reflect on their assumptions about underprivileged people, uncovering biases and prejudices. Some even reported regretting their past attitudes, wishing they had been more understanding and inclusive. Moreover, reflecting on comics like “Woman Rebel,” “Bad Doctor,” and “Mom’s Cancer” helped them re-examine their vision of professionalism.

Reading Woman Rebel by Peter Bagge definitely made me reflect on professionalism in dentistry but also advocacy. After reading this I personally felt that you can still be professional but advocate for what you believe is right… and be regarded as ‘unprofessional’ in that era but moving forward will be celebrated. (Student 3)

Students also appreciated the interactive nature of the platform used for writing logs (Microsoft OneNote), as it allowed the instructor to provide feedback, answer students’ questions, and guide their reflection process. Some mentioned that his encouragements motivated them to read comics more attentively, do independent research, and explore autobiographies further online.

Whenever we wrote something, [the instructor] would be like: “oh yes, I also think the same way, I think you should elaborate [on] this point”. I could speak up whatever perspective I have and have no fear. That's how I grew. (Student 2)

2.2.2. Class discussions

Class discussions allowed students to collectively reflect on comics and share their perspectives, re-examining beliefs, assumptions, and past actions, as well as debating healthcare professionals' roles and responsibilities. They discovered both commonalities and differences in their views, but also paradoxical differences in their perspectives and opinions. This process allowed them to examine comics through others’ lenses, enhancing their understanding of the topics.

There was a student that reminded us all the time that real life clinics are not as easy as you're thinking and you don't always have the time to make that search for resources and make phone calls to find social workers [for social prescription]. You needed those opinions and those point of views to help you not be overwhelmed with theories (Student 8)

These discussions had two key components that facilitated their transformation: listening to others and expressing oneself. Listening provided reassurance that feelings of confusion, uncertainty, and guilt were common, while expressing thoughts boosted confidence and agency. It also offered insights into their cognitive processes and how they rationalized phenomena.

It really felt good when I was able to express my perspectives in the class. It gave me confidence and I really enjoyed when other people told me the feel or act in a similar way. At other times, some classmates would challenge my perspectives … it made me think twice about what I wanted to say and elaborate on why I think the way that I think. (Student 1)

2.2.3. Oral presentations

Students considered the instructor’s presentations integral to their learning process. They found the presentations to be excellent "wrap-ups" of class discussions, providing the main "take-home" message for each session. Presentations helped students relate comics to the course objectives by summarizing key parts of each story relevant to the MTM, describing the health pathways of characters, and suggesting ways dentists could recognize and address their needs.

[The instructor] could make us think and or look using that lens of social dentistry, person centered care or advocacy etc. He made us really think about treating these patients and how to be socially involved. (Student 5)

Additionally, the presentations offered valuable insights into the instructor’s perspectives, which students highly valued given his expertise in biopsychosocial approaches. This validation boosted their confidence when their views aligned with his and encouraged them to broaden their horizons by reflecting on his arguments when their perspectives differed.

Whenever [the instructor] presented something that I had noticed and reflected on, I was like “Oh my God, we made the same connections, I'm so happy!” You could see what he was trying to say, I was able to understand what he was thinking as well. (Student 3)

2.2.4. Creative assignment

Students had mixed feelings about creating a comic as their final assignment. Educationally, they agreed that developing comics helped them reflect on class learnings and their professional experiences and values. For example, one student recounted a clinical encounter with a homeless patient and how the course taught her to address the patient's social needs. This process fostered their creativity in envisioning holistic approaches and addressing patients' social determinants of health.

At first, I felt that it's something so hard to do, but once I started, like I, I had the story in my mind. Once you have your pencil and your paper and you start, you feel that you know it, it goes by itself, you don't have to think much. (Student 6)

Artistically, some students found making comics enjoyable and accessible, while others found it difficult and demanding, even with support from a guest comic artist. Some also felt it was not suitable for assessing knowledge, preferring traditional methods like tests and quizzes. Nonetheless, all students found the assignment feasible, as the instructor emphasized that their ideas, rather than artistic skills, determined their final marks.

I was like, thank God it’s only two pages, cause I really can’t! I mean I went over the concepts and had some ideas in mind, but it was really challenging to draw a comic based on them. I always wished final assignment was in a different format […] I liked our own old methods, like multiple choice questions, or questions requiring short answers. I didn’t think this was a proper evaluation method (Student 7).

3- Feelings of safety and inclusion were fundamental for students’ transformative learning

Students emphasized the importance of feeling safe in class to freely express their opinions. They felt unjudged and confident that sharing diverging perspectives would not have negative repercussions on their grades. This empowerment process enabled them to voice questions or doubts and find answers through debate. They valued the sense of validity and confidence this approach provided, which was rare with traditional education methods.

You could be yourself and you can express your opinion, like whatever it is; and it happened, like in the class, many of us had really the opposite opinions, or and everyone could talk. Everyone can say whatever he wants without being judged. So, it was really, really comfortable. (Student 8)

Students attributed the feeling of safety to the instructor's warm, welcoming, and empathetic demeanor. His approach fostered an egalitarian atmosphere, encouraging students to freely express criticism or disagreement and think independently. Additionally, the instructor maintained a respectful and relaxed atmosphere, making class discussions enjoyable and motivating active participation from students.

What I would say in this class would not be things that I would say in other classes. If there was a different teacher present, I would not have said the things that I said fearing I might have overstepped, or that the teacher might look at me differently. (Student 6)

Some students criticized the instructor's impartiality in discussions, attributing it to his politeness. They felt that while discussions were informative, the instructor should have determined the "right" and "wrong" perspectives at the end of each class. They found lectures given by the instructor preferable at times, as they considered him an expert. Students’ feeling of safety was also favored by the instructor's approach to assessing their performance and grading. They noted that the instructor's focus on formative assignments rather than testing knowledge relieved the pressure of memorization and sparked their interest in the course material.

We were sitting in the presence of probably the most knowledgeable person with respect to person-centered care and social dentistry, and then we would lose the chance to listen to him because we had to listen to our classmates […] I also did not like that he let everyone say whatever they thought. To be honest, I think he is too kind to be a strong moderator. (Student 1)

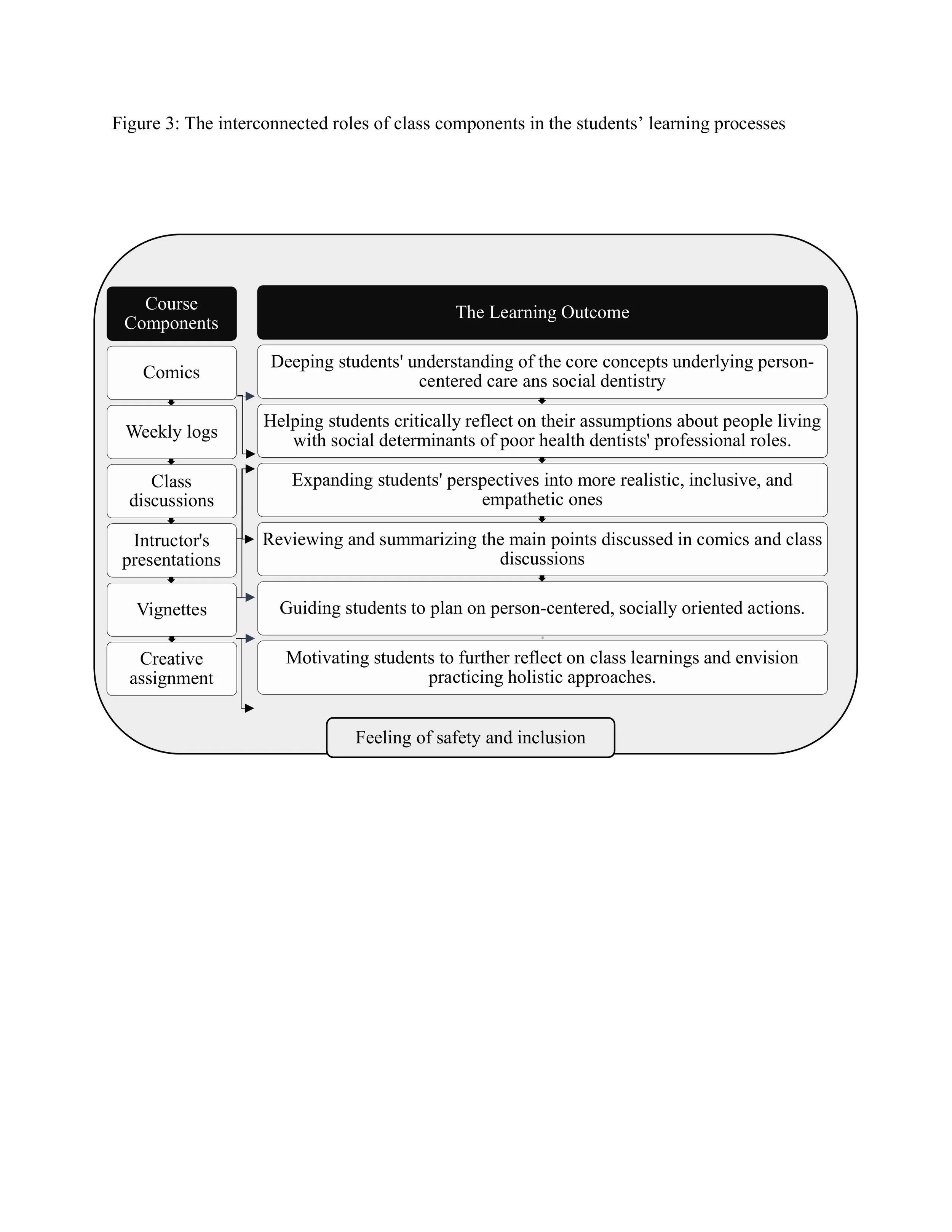

Figure 3 summarizes how feeling safe encircled students’ overall learning experience. We have also illustrated the class components and their interconnected roles in facilitating students’ transition to biopsychosocial approaches.

Discussion

Our study indicates that transformative learning theories and narratives may be effective methods for teaching biopsychosocial models like the MTM. Engaging with comics, in particular, could enhance students' ability to empathize with underprivileged individuals and comprehend the impact of social structures on health and illness. Through this transformative process, students may be able to reevaluate their roles and responsibilities, leaning towards more humanistic and socially oriented definitions of professionalism.

Previous work in narrative medicine, particularly in medical education, has shown that engagement with illness narratives – through close reading, reflective writing, and dialogue – can deepen empathy, foster critical self-awareness, and prepare clinicians to address both the human and structural dimensions of illness (Charon, Kumagai and Lypson). In our course, the use of comics, vignettes, and reflective logs functioned as narrative medicine tools that not only invited students to interpret patients’ stories but also prompted them to translate these insights into MTM-guided actions at the clinical, community, and policy levels. This represents a novel extension of narrative medicine into dentistry, where narrative-based teaching has been less prevalent, and demonstrates how the interpretive practices of narrative medicine can be aligned with the MTM’s explicit emphasis on structural advocacy and community engagement.

While our findings are in line with several authors' remarks (Bernabeo et al. "Utility of Vignettes," Bernabeo et al. "Using Vignettes to Foster Professionalism," Brondani et al., Vergnes et al.), our study also highlights several points that educators should consider to successfully implement similar courses.

We first emphasize the importance of establishing classroom environments that are safe and shield learners from personal attacks or humiliation, consequently diminishing their fear of failure and instilling a sense of legitimacy to support their transformative processes. To achieve this, authors (Hovey and Craig, Jamieson et al., Kumagai, Kumagai and Lypson, Lévesque et al., Mann et al.) recommend redefining educators' roles from the traditional directive expert to a supportive coach who builds trustful relationships with students and offers emotional support and theoretical insight . This requires educators to become critically conscious of their power, willing to relinquish authority, and become co-learners alongside students.

We also remind educators not to forget that students are generally accustomed to passive learning in traditional education systems, making it challenging for them to engage in autonomous thinking or question professional norms (Montuori). For the same reason, students may also struggle with creative assignments and feel insecure with new learning approaches, as our study indicates. Educators should consequently anticipate students' difficulties in adapting to these approaches and support them patiently along their journey.

Finally, we invite readers to be prudent when interpreting our findings, which are not generalizable (Green and Thorogood) but may nevertheless be transferable to other contexts. Moreover, due to the small number of students registered in the course (eight), we were unable to conduct purposeful sampling. However, the sample’s diversity in age, gender, educational background, and work experience (see Table 3) closely aligned with a maximum variation strategy, enhancing the likelihood of capturing varied perspectives. (Green and Thorogood, Patton)

Another limitation of this study was its assumption that most dental students are trained within the biomedical model and thus approach care through its reductionist lens. However, not all participants may have shared this orientation, and some could have already valued holistic or socially responsive practice. Because we did not assess students’ initial perspectives, we cannot determine whether reported changes reflected true transformation or pre-existing views. This represents a methodological limitation that future studies should address.

Preparing healthcare professionals to adopt biopsychosocial approaches is a difficult but necessary endeavour in dentistry like in other healthcare disciplines. In this context, our study is important because it is one of the rare examples of educational approaches that could effectively contribute to this goal. Therefore, we encourage dental schools and educators to introduce transformative learning approaches in their curricula and use narratives, including comics and vignettes, to support students' learning process.

Conclusion

Our study shows that integrating the Montreal–Toulouse Model with narrative medicine pedagogy—through comics, vignettes, reflective writing, and guided discussion—can help dental students move toward a more humanistic, socially responsive practice. By making patients’ lived experiences central to learning, this approach enables future dentists to connect individual care with community and societal advocacy. This work demonstrates how narrative medicine principles can be effectively adapted beyond medicine, expanding their reach into dentistry and other health professions while contributing to the broader dialogue on how stories can transform clinical practice.

Works Cited

Apelian, Nareg, et al. “Humanizing Clinical Dentistry through a Person-Centred Model.” International Journal of Whole Person Care, vol. 1, no. 2, 2014, https://doi.org/10.26443/ijwpc.v1i2.2.

Asa’ad, Farah. “Shared Decision-Making (SDM) in Dentistry: A Concise Narrative Review.” Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, vol. 25, no. 6, 2019, pp. 1088–93, https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.13129.

Bedos, C., et al. “Social Dentistry: An Old Heritage for a New Professional Approach.” British Dental Journal, vol. 225, no. 4, 2018, pp. 357–62, https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2018.648.

Bedos, Christophe, et al. “Towards a Biopsychosocial Approach in Dentistry: The Montreal-Toulouse Model.” British Dental Journal, vol. 228, no. 6, 2020, pp. 465–68, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-020-1368-2.

Berge, M. E., et al. “A Critical Appraisal of Holistic Teaching and Its Effects on Dental Student Learning at University of Bergen, Norway.” Journal of Dental Education, vol. 77, no. 5, 2013, pp. 612–20.

Bernabeo, E. C., et al. “The Utility of Vignettes to Stimulate Reflection on Professionalism: Theory and Practice.” Advances in Health Sciences Education: Theory and Practice, vol. 18, no. 3, 2013, pp. 463–84, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-012-9384-x.

Bernabeo, Elizabeth C., et al. “Professionalism and Maintenance of Certification: Using Vignettes Describing Interpersonal Dilemmas to Stimulate Reflection and Learning.” Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, vol. 34, no. 2, 2014, pp. 112–22, https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.21228.

Brondani, Mario, et al. “The Role of an Educational Vignette to Teach Dental Students on Issues of Substance Use and Mental Health Disorders in Patients at the University of British Columbia: An Exploratory Qualitative Study.” BMC Medical Education, vol. 21, no. 1, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02767-9.

Charon, R. “The Patient-Physician Relationship. Narrative Medicine: A Model for Empathy, Reflection, Profession, and Trust.” JAMA, vol. 286, no. 15, 2001, pp. 1897–902.

Cranton, Patricia. Understanding and Promoting Transformative Learning: A Guide to Theory and Practice. 3rd ed., Routledge, 2016.

Creswell, John W., and Dana L. Miller. “Determining Validity in Qualitative Inquiry.” Theory into Practice, vol. 39, no. 3, 2000, pp. 124–30.

Czerwiec, M. K. Graphic Medicine Manifesto. Pennsylvania State UP, 2015.

Engel, G. L. “The Need for a New Medical Model: A Challenge for Biomedicine.” Science, vol. 196, no. 4286, 1977, pp. 129–36.

Glick, Michael, and David M. Williams. “FDI Vision 2030: Delivering Optimal Oral Health for All.” International Dental Journal, vol. 71, no. 1, 2021, pp. 3–4, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.identj.2020.12.026.

Green, Judith, and Nicki Thorogood. Qualitative Methods for Health Research. 4th ed., SAGE, 2018.

Hovey, Richard, and Robert Craig. “Understanding the Relational Aspects of Learning with, from, and about the Other.” Nursing Philosophy: An International Journal for Healthcare Professionals, vol. 12, no. 4, 2011, pp. 262–70, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-769X.2011.00491.x.

Jamieson, Janica, et al. “Teacher, Gatekeeper, or Team Member: Supervisor Positioning in Programmatic Assessment.” Advances in Health Sciences Education, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-022-10193-9.

Kumagai, Arno K. “From Competencies to Human Interests: Ways of Knowing and Understanding in Medical Education.” Academic Medicine, vol. 89, no. 7, 2014, pp. 978–83, https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000234.

Kumagai, Arno K., and Monica L. Lypson. “Beyond Cultural Competence: Critical Consciousness, Social Justice, and Multicultural Education.” Academic Medicine, vol. 84, no. 6, 2009, pp. 782–87, https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a42398.

Lévesque, Martine, et al. “Advancing Patient-Centered Care through Transformative Educational Leadership: A Critical Review of Health Care Professional Preparation for Patient-Centered Care.” Journal of Healthcare Leadership, 2013, p. 35, https://doi.org/10.2147/JHL.S30889.

Mann, Karen, et al. “Reflection and Reflective Practice in Health Professions Education: A Systematic Review.” Advances in Health Sciences Education: Theory and Practice, vol. 14, no. 4, 2009, pp. 595–621, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-007-9090-2.

Mezirow, Jack. “Learning to Think Like an Adult: Core Concepts of Transformation Theory.” Learning as Transformation: Critical Perspectives on a Theory in Progress, edited by Jack Mezirow, Jossey-Bass, 2000, pp. 3–33.

Montuori, A. “The Quest for a New Education: From Oppositional Identities to Creative Inquiry.” Re-Vision, vol. 28, no. 3, 2005, pp. 4–20.

Patton, Michael Quinn. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice. 4th ed., SAGE Publications, 2015.

RSBO Art and Science Project. “Le Réseau de Recherche en Santé Buccodentaire et Osseuse (RSBO).” RSBO, https://www.rsbo.ca/en/art-and-science/. Accessed Aug. 2025.

Sandelowski, Margarete. “Whatever Happened to Qualitative Description?” Research in Nursing & Health, vol. 23, no. 4, 2000, pp. 334–40, https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-240X(200008)23:4<334::AID-NUR9>3.0.CO;2-G.

Taylor, EW. “An Update of Transformative Learning Theory: A Critical Review of the Empirical Research (1999–2005).” International Journal of Lifelong Education, vol. 26, no. 2, 2007, pp. 173–191.

Vergnes, Jean-Noel, et al. “What about Narrative Dentistry?” Journal of the American Dental Association (1939), vol. 146, no. 6, 2015, pp. 398–401, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adaj.2015.01.020.

World Health Organization, Institute. Integrating the Social Determinants of Health into Health Workforce Education and Training. World Health Organization.

Corresponding author: Homa Fathi. Faculty of Dental Medicine and Oral Health Sciences, McGill University, 2001 Avenue McGill College #529, Montréal, QC H3A 1G1; Email: Homa.fathi@mail.mcgill.ca

Ethics approval

This study was conducted in accordance with McGill faculty of medicine's Institutional Review Board (IRB) under the review number A05-B46-21B (21-05-039). All students read and signed a written informed consent before participating in the study.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not openly available due to ethical considerations and aligned with the instructions of McGill Faculty of medicine's Institutional Review Board (IRB). However, multiple anonymized parts of the data have been added to the manuscript (see quotations in table 3).

Funding

The authors did not receive financial support from any organizations for conducting this study.

Competing interests

The authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial or non-financial interest in the subject matter discussed in this manuscript.

Authors’ contributions

Christophe Bedos designed and supervised this study; he contributed to the data collection, the analysis, and the writing of the manuscript. Homa Fathi carried out the data collection and data analysis and contributed to drafting the manuscript. Anahita Ranjbar contributed to the data collection and analysis as well as drafting the manuscript. Richard Hovey contributed to the study design, oversaw the data analysis, and helped writing the manuscript.

Reference and/or download PRINT PDF for Tables and Figures

Homa Fathi is a doctoral researcher at the faculty of dental medicine and oral health sciences at McGill University. Her scholarly work focuses on improving access to oral healthcare for people with disabilities, advancing decolonization in dentistry and promoting social dentistry as a framework for addressing health inequities. She also engages in projects that integrate biopsychosocial and narrative approaches into dental education, exploring how transformative learning, storytelling and reflective practice can foster empathy and patient-centered care. Trained as a general dentist, Fathi brings clinical experience to her academic work, bridging theory and practice. She is committed to developing more inclusive, humanistic and socially responsive models of dental care that recognize and address the social determinants influencing oral health outcomes.