“She created her poems from her being, crippled by depression and yet gifted with a vision of light as mercy. She put universal feeling into beautiful words, offering poems of solace and consolation to the world. It is this that will secure her reputation as a poet.” p156

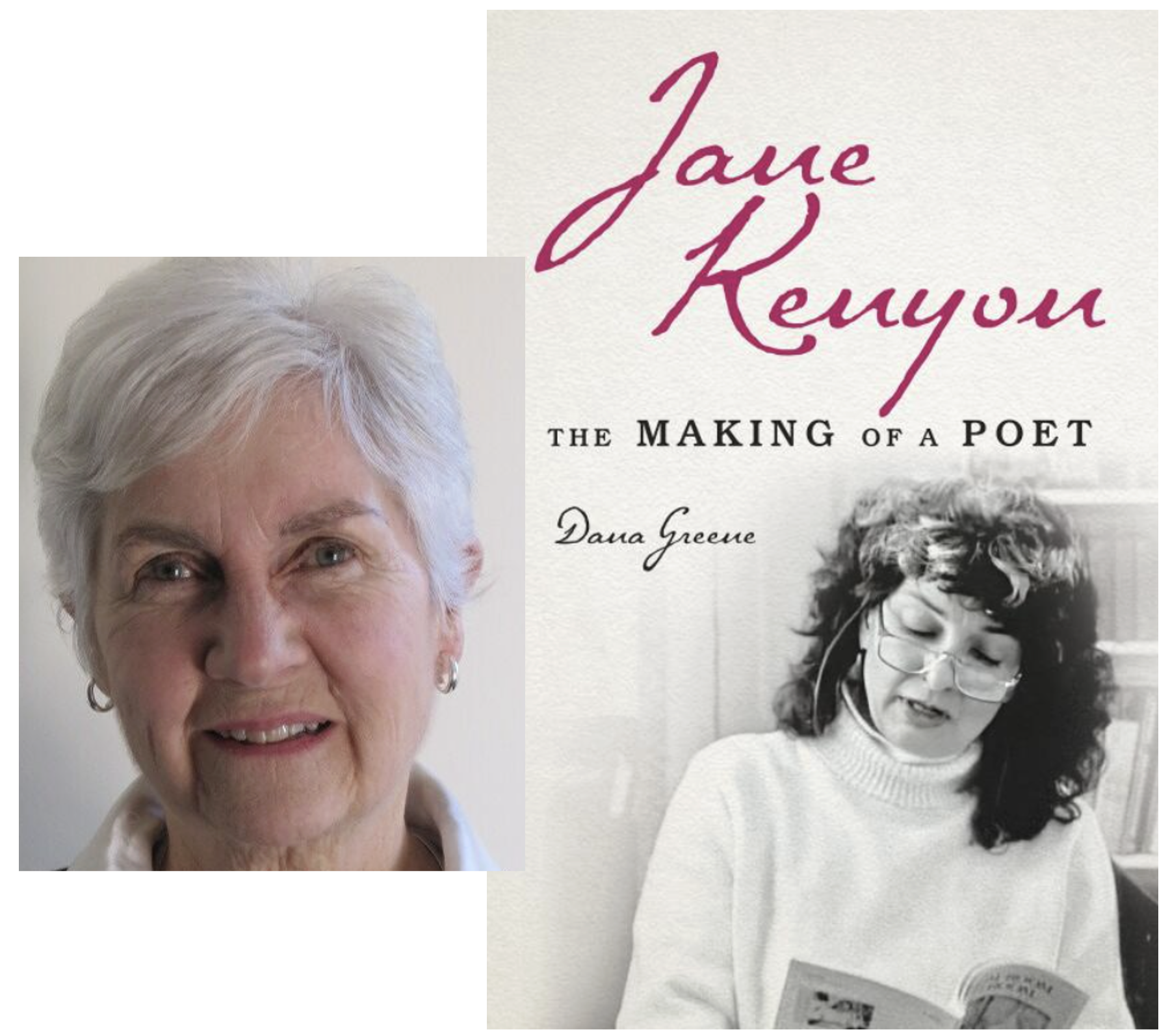

In Jane Kenyon: The Making of a Poet (University of Illinois Press, 2023), the late Dana Greene (1942-2023), a dean emerita of Oxford College of Emory University, whose books include Denise Levertov: A Poet’s Life and Elizabeth Jennings: The Inward War, capitalizes on revealing new material to tell the poet’s story from Kenyon’s own perspective. The first major Jane Kenyon biography since 2002 (1), this layered biography goes well beyond others: Much of Kenyon’s narrative had been previously told from the viewpoint of her well-known husband—the former U.S. Poet Laureate, Donald Hall—but in this reexamination, readers may come to a greater appreciation of Kenyon’s work as an entity that is distinct and separate from his influence. Jane Kenyon: The Making of a Poet makes a wonderful companion to her poetry, as Greene explores the poet’s oeuvre with the benefit of two decades’ worth of literary criticism and a trove of personal correspondence. This is an important volume for fans of her work, for patients and caregivers seeking to more fully understand mental illness, and for health humanities educators wishing to utilize Kenyon’s poems in their curricula.

“This biography is Jane Kenyon’s story, an attempt to … penetrate her full poetic gift, and to show how it came to be … Donald Hall cannot be excluded from this story … but here Kenyon will be moved to the foreground and Hall to the background.” p3

Jane Kenyon (1947–1995) was raised in Ann Arbor, Michigan, and studied there at the University of Michigan before marrying Donald Hall in 1972. Three years later, the couple moved to his family’s farmhouse in Wilmot, New Hampshire, where they enjoyed what has been represented as a bucolic “house of poetry” until Kenyon’s life was cut short by leukemia at the age of 47. He survived her by more than two decades, writing considerably about her loss and crafting a careful narrative surrounding their life together.

The truth of their marriage is perhaps more nuanced and less idyllic than readers have been led to believe, which served as the inspiration for Greene’s investigative work. Greene attempts to shed light on their relationship, disentangling Kenyon’s identity from Hall’s and allowing for an analysis of her poetry in its own right. He was a prolific writer, both in the years of their marriage and through the remainder of his lifetime, whereas Kenyon was more reticent about her personal sentiments. Her archives are reflective of sparse journaling, scattered correspondence, and a limited body of prose that was only beginning to develop at the time of her death. This disparity made Greene’s task a difficult one, but she found creative ways to accomplish it. She made extensive use of the Jane Kenyon Papers at the University of New Hampshire Library and conducted interviews with some of Kenyon’s closest companions, who also provided previously unavailable personal correspondence. When these sources still failed to be revealing, Greene ably turned to Kenyon’s poetry to continue her story, using both published and working copies of her poems throughout the text.

In many ways, the narrative that emerges from Greene’s biography is not substantially different from the one that Hall describes. In fact, she was forced to rely on his writing in several areas where other source material was unavailable. The significance of her contribution, however, is that she commits herself to detail and authenticity regardless of what she unearthed, particularly surrounding the points of friction attendant to their working relationship. With two poets living in the same house—especially with one being nationally well known and the former professor of the other—there were bound to be differences of opinion, disparities in recognition, even conflict when simultaneous acceptance and rejection letters arrived from literary magazines. Hall makes considerable mention of these instances in his prose, but often smooths the edges to produce a cohesive image of two poets united as one. His reason for doing so may have stemmed from wishful thinking or may have been a deliberate attempt on his part to protect Kenyon’s legacy. In either case, Greene feels that he fell short of telling her true story, which has resulted in a narrowed study of her character.

This greater knowledge of Kenyon’s thoughts, feelings, and conflicts allowed Greene to arrive at a fuller appreciation of her poems, which is demonstrated through an in-depth analysis of each published collection. Far from diminishing Kenyon’s legacy with the unsavory details of her marriage, Greene enables readers to know the truth that Jane so often sought in her writing. This empowers them to make their own decisions through an understanding of the poet’s struggles, not only in dealing with depression and bereavement, but in endeavoring to make a name for herself from within the shadow of her loquacious and oft-lauded husband. Devotees of Donald Hall may take umbrage at the continual discounting of his version of events, but Greene presents sufficient evidence for even the most ardent Hall acolytes to reconsider their relationship. Theirs was by all measures a successful and happy marriage, but nonetheless was likely more complex than the simple vision of marital unity that Hall suggests.

“Depression was a major preoccupation in Kenyon’s life, the subject of many of her poems, and a lure for readers who shared that disease. Nonetheless, she would not have wanted to be remembered solely as a poet of depression … She was clear: depression was not to be cultivated in the service of poetry.” p153

It is tempting to speculate about Kenyon’s further poetic output had her leukemia stayed in remission, just as it is easy to wonder if her prose would have continued to develop. Though she published just four volumes of poetry in her lifetime, her recognitions included a Guggenheim Fellowship, the inaugural PEN/Voelcker Award for Poetry, and selection as the Poet Laureate of New Hampshire. She wrote candidly about her lifelong struggles with mental illness, leading her works to be used in health humanities courses along with a broader reflection on her death from leukemia through writings by Hall (2,3). As her depression worsened, she was able to feel greater compassion towards herself and others, which is powerfully captured by Greene’s instructive analysis of her work. She dubs Kenyon the “Poet Laureate of Depression,” comparing her to other writers who address mental illness and delving into the specific impact that depression had on her poems. The picture that results is of a woman suffering from mental illness, yet using her writing to explain her condition in an attempt to enable healing. This latter characteristic is perhaps what makes Kenyon’s poetry so effective within the medical humanities and what has allowed it to have such an enduring impact over the past 30 years.

Jane Kenyon: The Making of a Poet serves as a welcome and overdue addition to a growing body of Kenyon scholarship. Exhaustive is a difficult word to apply to such a compact volume, but Greene makes effective use of the available source material and shows a true command of the works of her subject. By providing fresh insights into many of Kenyon’s writings, this biography makes an excellent companion to her collected poems, translations, or limited prose, as it allows readers to more fully understand the trajectory of her life and lifework. Those interested in learning more about Kenyon can look to the aforementioned works by Hall (2,3), a full-length biography from John H. Timmerman,1 and several collections of other writings surrounding her work (4-6). Greene should be applauded for telling what is surely close to the true story of Kenyon’s marriage and the lifetime she spent pursuing truth through poetry. Her biography gives readers the latitude they need for Kenyon to live in their memories as both a flawed human and an almost-divinely-gifted poet. - Justin C. Cordova, MD

_________________________________

Timmerman J. Jane Kenyon: A Literary Life. Eerdmans: Grand Rapids, 2002.

Hall D. Without. Houghton Mifflin: Boston, 1998.

Hall D. The Best Day, the Worst Day: Life with Jane Kenyon. Mariner Books: Boston, 2006.

Peseroff J, ed. Simply Lasting: Writers on Jane Kenyon. Graywolf Press: Minneapolis, 2005.

Hornback B, ed. “Bright Unequivocal Eye”: Poems, Papers, and Remembrances from the First Jane Kenyon Conference. Peter Lang: New York, 2000.

Carruth H. Letters to Jane. Ausable Press: Keene, 2004.

Justin C. Cordova, MD is a writer and physician in the National Capital Region. He has been previously published in a number of academic and literary journals, including Academic Medicine, Anesthesiology, and the Methodist DeBakey Cardiovascular Journal. Cordova, who has a passion for books and is particularly interested in the intersection of literature with medicine, endeavors to use his writing to establish a lasting connection with his patients, to encourage other physicians, and to further explore the health humanities. His time at home includes a wonderful wife, a beautiful toddler, and newborn twins, so he thinks life could not get much better.