Germaine’s Daughter by writer, artist and Los Angeles-based psychotherapist Lydia Kann, is a graphic memoir that is essential reading for people like me — descendants of victims of pogroms or the Holocaust who witnessed anguished relatives speaking in hushed tones in Yiddish. As a teenager I felt the pain radiating from my great-grandmother’s crumpled form in her recliner but never knew what she endured while escaping Eastern Europe. Through the raw prose and evocative paintings in this moving narrative, we see our life experiences reflected and confirmed. That said, the book, which was self published by Kann in October 2025, transcends any personal story of generational trauma to depict how the narrator brought a family tragedy to light, processed it and transmuted pain into something beautiful and meaningful.

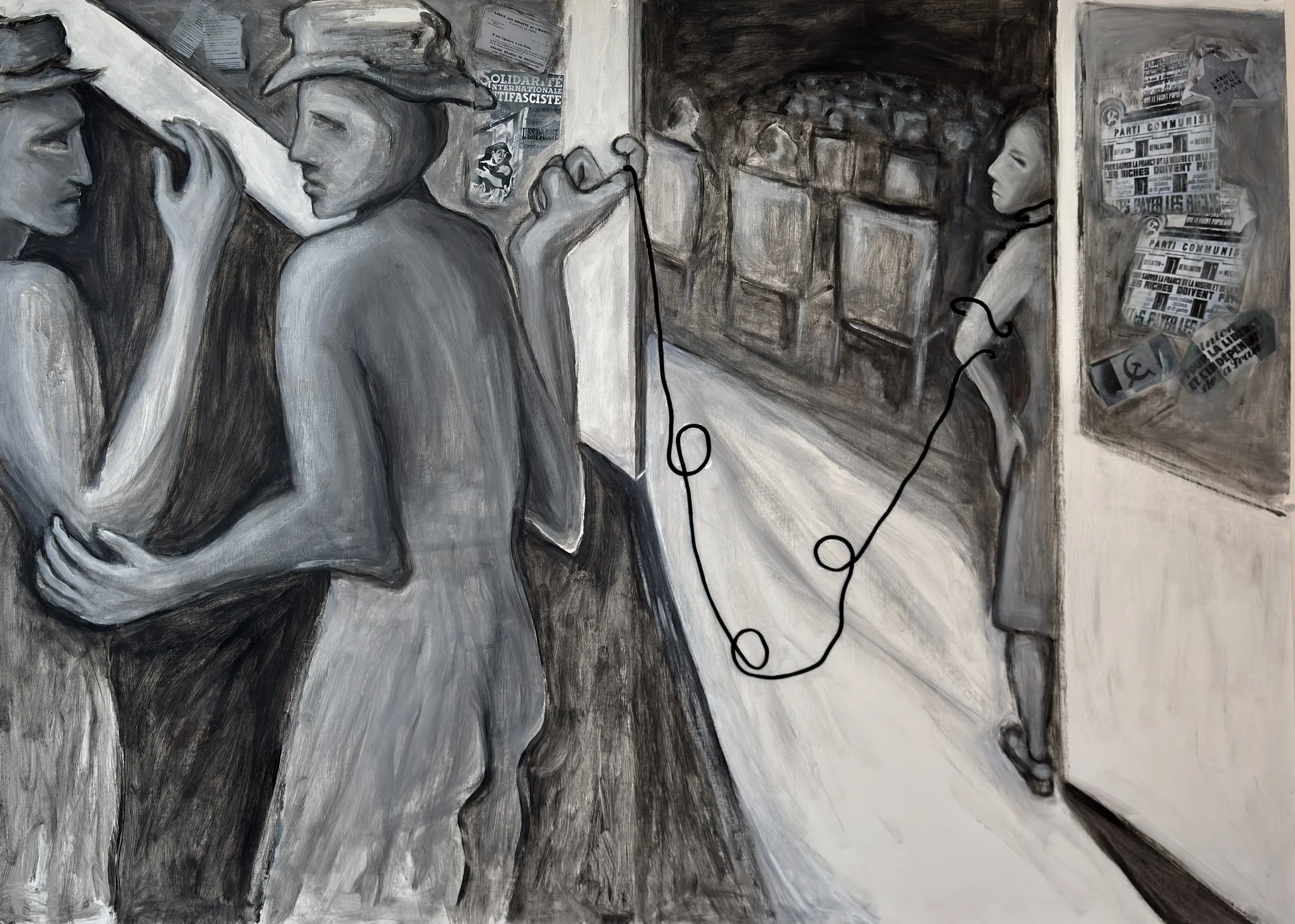

©Lydia Kann 'Hooked at the Meeting', (42" X 60", acrylic paint on paper), depicts Germaine, the mother in this story, joining the group of left-wing communist/socialist workers' political groups in Paris as she arrives from Poland in the late 1920s.

“I want to tell you about what happened to her, and then, to her daughter,” the narrator begins, pulling us into the stories of these women, both simply referred to as “her,” their contours yet to be defined. She pursues the timeline and details of the mother and the daughter’s experiences to help contextualize the emotional anguish that enveloped their lives. She acknowledges the difficulty of unearthing what happened to the mother since “(s)ometimes people don’t talk about the awful times in their lives.”

For example, the narrator can never really know whether her mother was in a concentration camp in France or was successfully hidden. Her sisters believe she spent time in the camp. It’s unclear if the mother is able to remember events of that time, marred as they are by the trauma of her losses—of her country, her family, her great love, and eventually her sanity.

While the words share the events, the paintings serve as the emotional core of the book. They evoke Impressionist, Expressionist and Cubist art in their stylistic approach—experimenting with light, angles, shapes and movement, to emphasize the dynamic experiential and emotional aspects of their themes, rather than creating realistic renderings of people or places. The individual figures in the book often look like they’re dancing—long limbs gracefully raised, flexed, pulling or leaping, even while herded onto a train towards an uncertain or deathly future or in the thralls of unreliable or unsafe relationships.

©Lydia Kann 'In the Closet', (45" X 60", acrylic paint and textile on paper), depicts Germaine in NYC once she becomes psychotic, as her teenage daughter tries to sleep in the closet to shut out the sound of her mother screaming at night.

Perhaps the depiction of this bodily elegance amid the horror signifies resistance to being ripped of one’s beauty, self-expression and unique identity. The mixture of abstract and realistic elements in the paintings also acknowledges that the narrator’s perspective is one person’s memory of experiences, which may be blurred by emotions and insufficient information: “One night when the mother is out, the daughter is asleep in their Murphy bed...and there’s an earthquake. The daughter remembers the bed folding up into the wall, but then again, does that really happen?” The narrator repeatedly notes that the truth she shares may not represent factual evidence as memories are altered by traumatic experiences.

The family story and narrator’s experience of it is also visually conveyed via the metaphor of a rope or thread. As it carries the story the yarn attaches the narrator, and others close to her, to both helpful and threatening characters. It initially connects the mother to people she meets in Paris when she moves from Poland to escape violence. Eventually the thread largely signifies the daughter’s connection to her mother. This emerges when the mother first shows signs of mental illness and continues through to the end of the book. “Sometimes she can’t wait to get away,” the narrator writes on a page opposite an image of the mother slumped over, head down, arms crossed, and the daughter—much larger in the foreground—is a dark figure trying to leave.

But the two are connected by ropes around both of their necks. At times the bond breaks, or is not visible for pages at a time, but it never completely disappears. What the narrator ultimately seeks is not an escape from what or who binds her but a transformation in how she lives her life and feels in their wake. Early in the book, the daughter describes how when her mother is psychically unraveling she hears an electric buzzing in her head or wants to run away, but about a third of the way through the book she finds another solution.

©Lydia Kann ‘Germaine in the Hospital', (hand on head), (60" X 44", pastel on paper), four pastel drawings as one depiction of Germaine in the mental hospital, drawn by the daughter while visiting.

At this point, images in the memoir start to include bright colors and more playful explorations of perspective and form. An allowance for stillness and meditation emerge in the renderings despite the fact that the mother is still not doing well. The narrator writes: “The daughter is happiest when being creative. She has loved making art and writing since childhood but didn’t know being an artist or writer could be a real job...Now she draws her visits to her mother in the hospital.” She practices image after image of her mother sitting, lying, standing. She’s starting to experience the power of her creativity to help her process and express her feelings instead of trying to escape them.

The daughter also becomes a therapist, a job that directly helps people as her mother had always advised, a choice many of us are urged to make in families that have experienced generational trauma. Ultimately, the daughter finds meaning in helping children in ways she was denied, and also finds healing through her art, including sharing her story through her words and paintings: “something torn is mended in the telling ” she tells us.

By the end of the book, the narration switches from third person to first person: “I wrap myself in the story and lie down on the sand,” the author writes. Germaine’s daughter closes the distance between what she is representing on the page and herself. She has integrated her story into her being and finds healing, creating hope for her readers that they too can find ways to transcend the pain and fragmentation borne of trauma and feel whole in the end.

—Eve Makoff

Eve Makoff is an internal medicine and palliative care physician and co-editor of Narrative Medicine: A Guidebook to Transforming Hearts and Minds. Makoff is a poetry editor for Intima: A Journal of Narrative Medicine.