In my grandmother's bedroom, the first thing you noticed was the green light. It glowed from the small camera mounted high in the corner, a quiet assurance that someone, somewhere, could always be watching. The device was installed after a string of near falls marked the progression of her dementia; at the time, no one in the family framed it as a moral question. It felt like the responsible thing to do. I stood in the doorway with a corner of freshly changed sheets bunched in my hand.

Jennie Erin Smith is the author of Stolen World. She is a regular contributor to The New York Times and has written for The Wall Street Journal, The Times Literary Supplement, The New Yorker, and others. She is a recipient of the Rona Jaffe Foundation Writers’ Award; the Waldo Proffitt Award for Excellence in Environmental Journalism in Florida; and two first-place awards from the Society for Features Journalism. She lives in Florida and Colombia.

Before the camera appeared, she had her own order. Every morning she changed the sheets, pulled the corners tight, smoothed the surface with both hands, and lingered for a moment before leaving the room. That time was hers. No one reminded her. No one helped. Then the camera came, and almost immediately she began unplugging it. When I pressed her for a reason, she hesitated and said, quietly, "I don't want people to see me when I look ugly."

I froze. It wasn't abstract ethics that stopped me; it was the raw shame in her voice. I didn't yet have the language for it. I only knew it felt wrong.

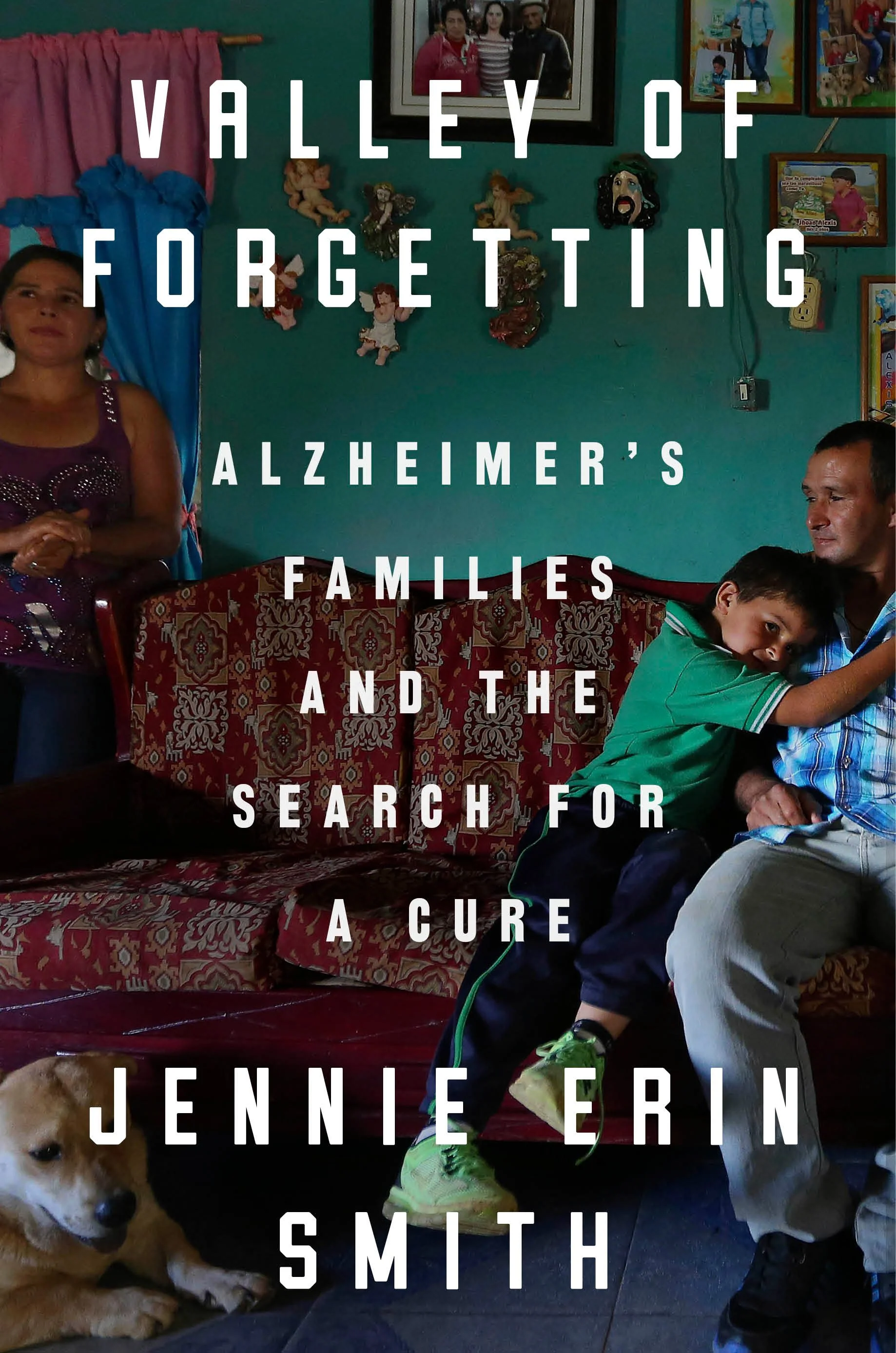

Jennie Erin Smith's Valley of Forgetting: Alzheimer’s Families and the Search for a Cure moves into a different bedroom—thousands of miles away in the mountains of Colombia—but it is animated by the same uneasiness: What happens to a person's agency when safety, science and hope converge on their body? Following the largest known kindred with a genetic form of early-onset Alzheimer's, Smith traces not only a medical mystery but a slow remaking of a community into a research site. The families she accompanies do not merely "participate" in trials; their lives are increasingly organized around the needs of clinicians, pharmaceutical companies and global neurologists. The book asks, with unusual patience, whose reasons continue to matter when the cure becomes the overriding narrative.

The setting is Antioquia, a rugged region shaped by isolation, poverty and violence. In towns like Yarumal and Angostura, a specific mutation—presenilin 1 E280A—has been passed down through generations. Locals long called it La Bobera—"the foolishness." Smith describes individuals like Ofelia, who by her early forties could no longer hold a job, began collecting trash and lost the ability to write words. The disease overtook her long before old age. For years the outside world barely noticed. Only when researchers realized that this genetically concentrated population might be ideal for testing amyloid-targeting drugs did the spotlight turn.

Smith records that arrival with the precision of a reporter and the sensitivity of a novelist. She chronicles Dr. Francisco Lopera's decades-long work mapping family trees and identifying the mutation. Smith vividly describes Lopera traversing muddy mountain roads by mule to reach isolated farmhouses, carrying not just medical instruments but a deep, personal witness to their suffering. Lopera is not a villain; he is a complex intermediary—deeply committed to his patients, yet also the conduit through which pharmaceutical interests enter the valley. Reading about his devotion, I felt both gratitude and unease.

The parallel with my grandmother's camera becomes stark as Smith shifts from bedrooms to village streets. Just as the camera turned a bedroom into a zone of surveillance, disrupting the private rhythm of my grandmother's morning ritual, the "Alzheimer's Prevention Initiative" transformed Colombian villages into a global laboratory. Blood is drawn, lumbar punctures are performed, cognitive tests are administered with rigorous regularity. In return, families receive medical attention they could not otherwise afford and the nebulous promise of a cure for the next generation.

But Smith is careful to show what the green light of science misses. The pharmaceutical gaze is often like a microscope: it zooms in on the valuable biological markers—the amyloid plaques, the tau tangles—while blurring the messy reality surrounding them. It sees the vial of blood, but misses the woman washing soiled sheets in a river; it tracks the genetic sequence, but overlooks the poverty that makes buying diapers impossible or the cartel violence that complicates travel to clinics. These are not peripheral details; they shape what care looks like on the ground.

One of the book's most poignant threads is how participants often misunderstand the nature of the transaction. Smith introduces us to family members who offer their bodies to the trial with a desperate, devotional hope, believing immediate relief is the goal. The scientists, bound by double-blind protocols, are there for data. It is a misalignment of expectations that echoes the disconnect in my grandmother's room: I wanted her safe; she wanted to be the woman who smoothed her own sheets. In Antioquia, families want relief from the "foolishness"; the trial is designed to test a hypothesis.

Smith captures the friction between these worlds. She describes the uncomfortable juxtaposition of high-tech American science dropping into rural plazas—million-dollar scanners humming where clean water is sometimes scarce. She notes the subtle coercion embedded in "informed consent" when subjects are desperate and the doctors control access to the only functioning healthcare in the region. The families are not forced, but like my grandmother, they are nudged into a corner where refusing the "protection" of science feels like ingratitude or recklessness.

Crucially, Valley of Forgetting does not dismiss the necessity of research. The search for a cure is noble; Lopera's dedication is heroic. Yet Smith refuses to let the cure narrative erase the care reality. She forces the reader to look at the ugly parts—the incontinence, the rage, the forgotten names, the societal neglect—that no camera wants to capture and no trial data point can encompass. She restores the moments my grandmother feared showing, suggesting that dignity comes from witnessing the whole person, not just the malfunctioning gene.

The book's arc does not end with triumph. The drug in question, crenezumab, ultimately failed its clinical endpoints in 2022. The scientific caravan may move on to the next promising cluster, but the families of Antioquia remain, caring for their own as they have for generations.

Valley of Forgetting unsettles easy technological optimism. It shifts our gaze from molecular targets back to the messy, demanding realities of the present. Without accusing, it gives shape to the quiet discomfort of the trial site, letting the reader sense what protocols feel like from the other side of the needle. It insists that how we treat the person in front of us is as vital as the search for a remedy.

Looking back at the incident with the camera, I see now that my grandmother's small act of unplugging it was not a refusal of care but a way of preserving the order she still made for herself. That repeated gesture—choosing when to be seen and when not to be seen—was a claim to agency no monitoring system could offer.

Smith's book lingers in that uneasy space, asking not only what a cure might one day accomplish, but what we are willing to overlook in the lives of those who are forgetting now.

Ian Hu

Ian Hu is a writer based in the San Francisco Bay Area. His work grows out of his family’s daily reality of dementia care and the difficult choices hidden inside ordinary routines. He writes about the fragile line between keeping a loved one safe and honoring who they are, and about how medical tools quietly change the feeling of a home. He is drawn to the weight of making choices on another person’s behalf.