In my essay “What Sticks,” I wrote about my Auntie Neng, a longtime nurse who invited me to go to the Philippines for a reunion. At the time, I was in medical school, struggling with my choices but also discovering the beauty of caregiving, a tradition in my family in our own lives and our choice of vocation.

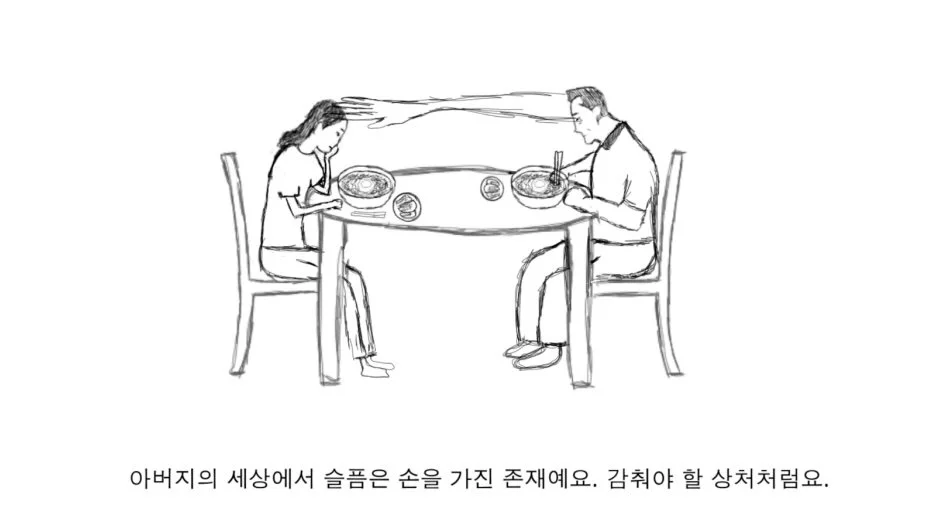

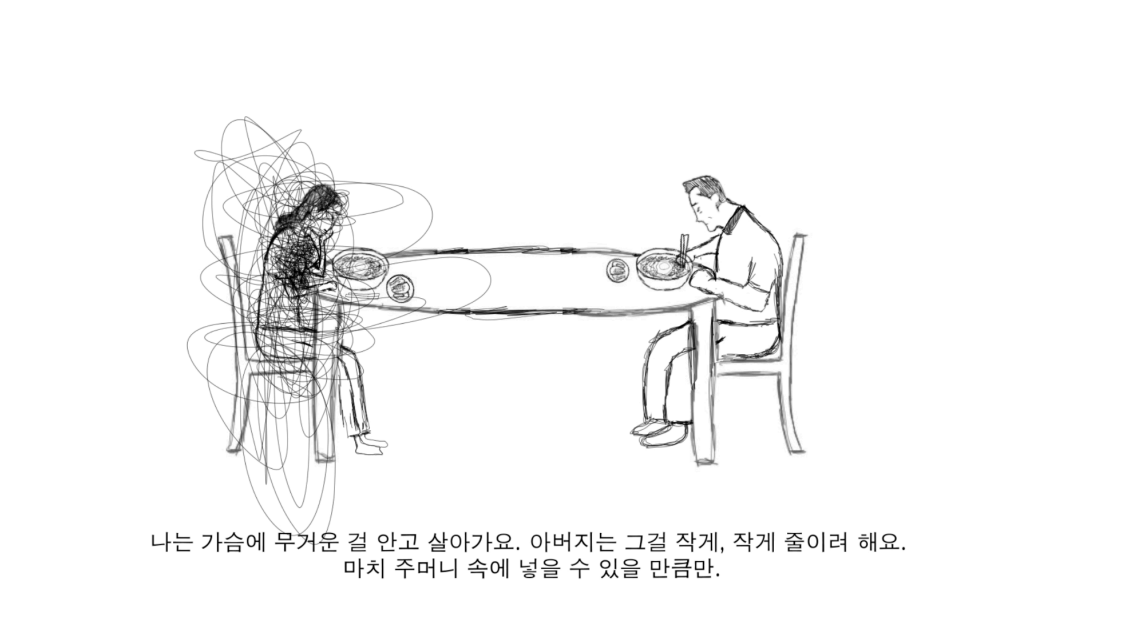

In this letter to my immigrant grandmother, who has passed away. I integrate scenes from Ellen Chang’s ‘The Dinner Table.” Chang, a researcher and storyteller who graduated from Harvard Medical School’s Media, Medicine, and Health program, explores the barriers that our immigrant ancestors face when trying to understand mental health, including cultural, generational, and linguistic; similarly, I explore the barriers between understanding grief and communicating with ancestors beyond life. Inspired by Chang’s imagery, I particularly focus on what it means to ‘reach’ out for an ancestor across the barrier of their death.

Dear Grandma,

Today, I saw someone who looked just like you; I even held her hand before sawing open her chest, cupping her heart like a sullen dove. I know you were cremated 10 years ago, Grandma, but I stood in that fluorescent basement wondering if the hand I was holding was really yours. It is impossible, right?

You used to tell me that after you die, the wind on my face is you saying hello. Little did we know that you would come back to me in far more tangible forms. In ways that might horrify you.

Still from the video © The Dinner Table by Ellen Chang FALL 2025 Intima

Your hands were thick and swollen, pricked by candied rose bushes and wrapped in expired hospital gauze. To be honest, Grandma, I never paid attention to your hands.

They were never empty — unless it was 6 am, and I was next to you, waiting for you to let go of me: “Don’t go.” The phrase that cracked you open: gooey Canterbury egg creme shelled in dark chocolate. You spent your childhood crouching in cacao fields--the hands of your mother’s mother.

The hand of the donor’s body looked like yours: thick as if swollen--just like your sister’s. Those hands…they couldn’t hold on to the things you wanted: to life, to religion, to some divine answer.

Still from the video © The Dinner Table by Ellen Chang FALL 2025 Intima

“All the flowers are dead.” Your little sister said long after you died. “I drove by their house once they sold it. You know all the roses your Grandma watered and grew? they’re all dead now.” A pit in my chest formed. Grandma, you would be so upset they let yourroses die — the roses you watered for hours every day in your nursing scrubs, that I would sniff every time I snuck through the garden gate to surprise you, that I used to pluck and soak in water in hopes of making something holy. The flowers all died: no you -- no roses.

But in all honesty: I was relieved the flowers died once you were gone. Sometimes, when a heart stops, part of the world also stops. I used to think the world always went forward. But not your candied roses. Sometimes when people are lost, the flowers they watered and grew and loved are also lost -- waiting to be found in the gap between us.

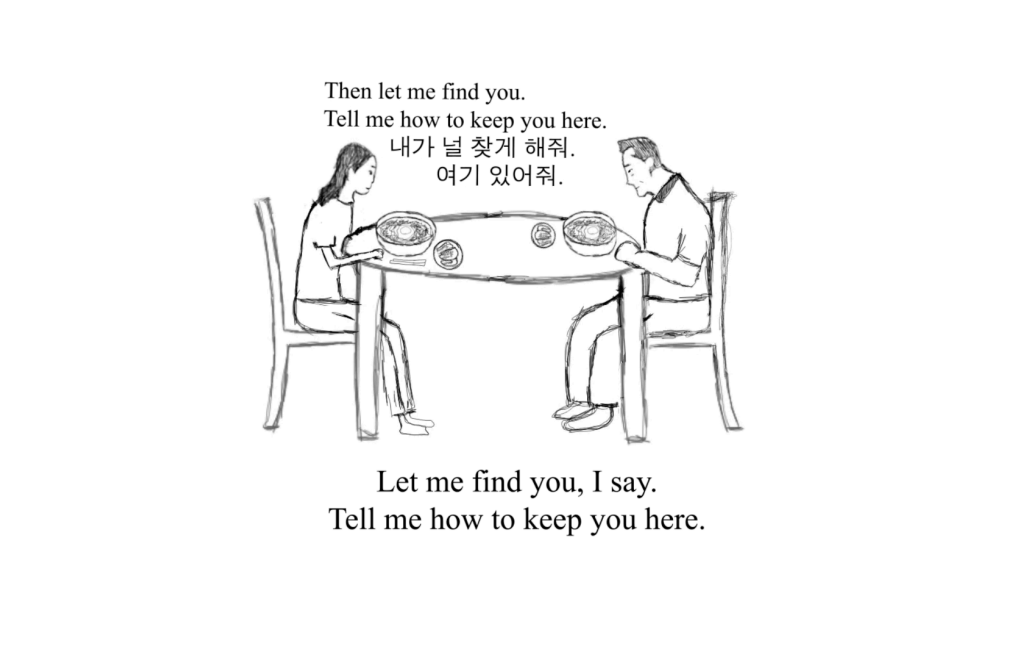

Then let me find you. Tell me how to keep you here.

From © The Dinner Table by Ellen Chang FALL 2025 Intima. Added text by Madison Palmer.

Let me find you, I say. Tell me how to keep you here.

Madison 'Sonni' Palmer

Madison 'Sonni' Palmer is a queer, mixed-race Filipinx writer who holds a BS from the University of Massachusetts Amherst and is studying at Stanford Medical School. She writes to heal. Palmer’s essay, “What Sticks,” appears in the Fall-Winter 2025-26 Intima: A Journal of Narrative Medicine.