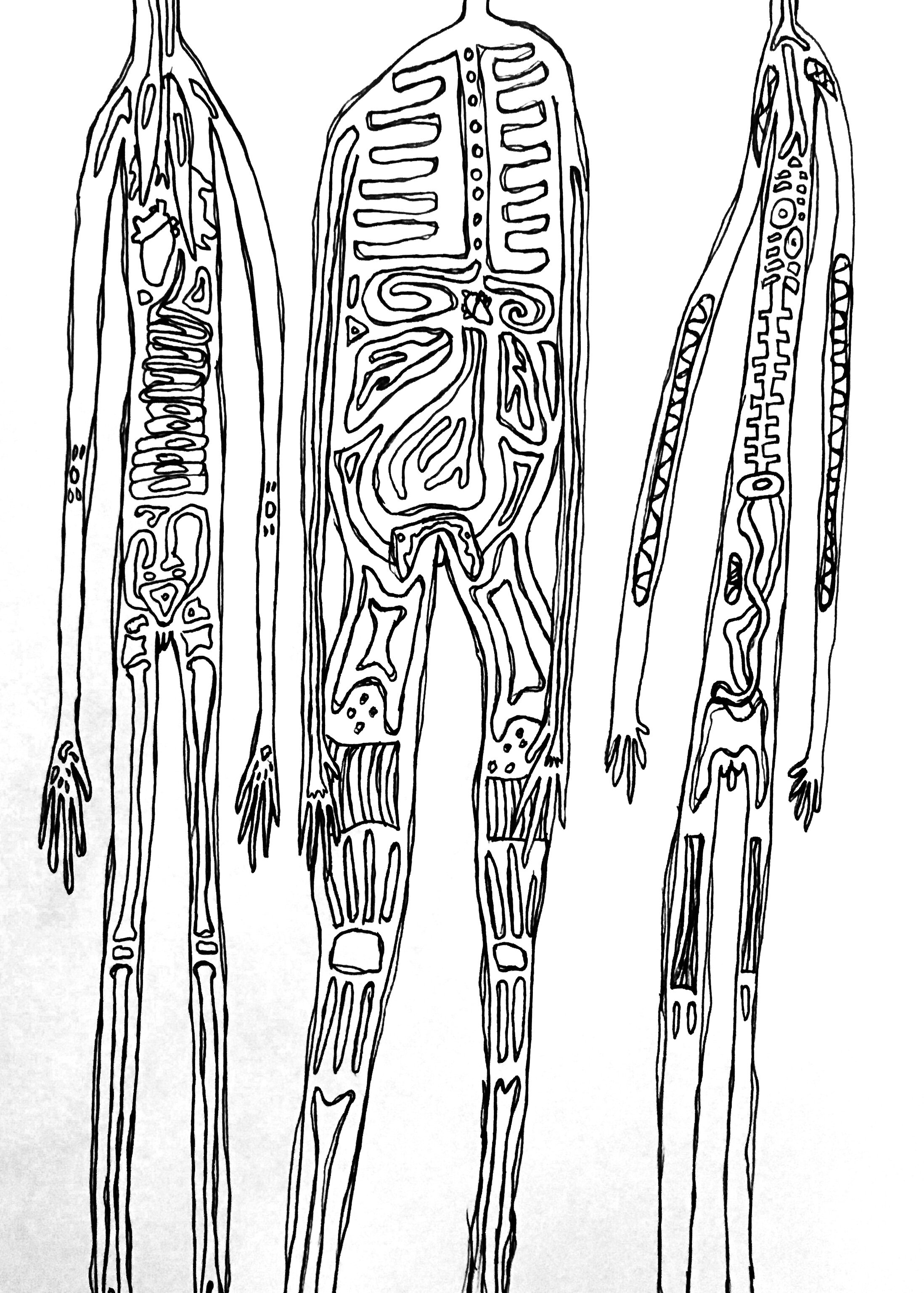

Raina Greifer’s artwork “Bodies” (Spring 2018 Intima) compels viewers to confront their own preconceptions and biases about body form. Her three headless, faceless bodies, of various sizes and depths, present a seemingly endless network of intertwined organs and bones, of breastplates and intestines and veins. Greifer urges the viewer to consider vulnerability, in the context of these drawings.

©Bodies by Raina Greifer. Spring 2018 Intima

Of course the body is much more than a composite of bones and organs, but a human cannot survive without the exquisite interplay of these parts. Greifer’s drawing asks me to consider not only the body’s intricate internal structure, but the external form shown to the world. Although the drawings are deliberately missing heads, the artist highlights the theme of vulnerability, which can only be contemplated through the integral component of the mind. Our minds magnify our vulnerability; our thoughts determine how we visualize ourselves, how we feel in our own skin.

After a lifetime of my own struggle with body dysmorphia, I was forced to confront both the mind and body’s strength and fragility when dealing with my daughter’s restrictive eating disorder, explored in my piece “Holding my Breath” (Spring 2020 Intima). Helplessly, I witnessed the ways in which the body fails without sufficient nutrition; how the body is reduced to conserving energy for the heart, brain, muscles, digestion. The body truly becomes a vessel of organs and bones all vying to survive.

But the starved mind is trying to survive too. Recovery is dependent on replenishing not only the organs with required energy, but the mind with recognition of the body's miracle and potential, whatever its size. I value Raina Greifer’s artwork, which encourages me to consider the vulnerability of the mind, and its intimate connection with the complexity of the body.

Diane Forman is a writer and educator. After a long career as writing tutor and educational consultant, Forman is currently working on a series of essays and a memoir. Additionally, she leads adult writing groups and retreats on the north shore of Boston. She holds a BS in English and Education from Northwestern University, and an Ed.M. from the Harvard Graduate School of Education and is an AWA affiliate, trained and certified to lead workshops in the AWA (Amherst Artists and Writers) method. Her non-fiction essay “Holding My Breath” appeared in the Spring 2020 Intima: A Journal of Narrative Medicine.